Zipper-Related Penis Injuries: A Medical Concern of Modern-Day Men

Author:

Lawrence M. Wyner, MD

Citation:

Wyner LM. Zipper-related penis injuries: a medical concern of modern-day men. Consultant. 2017;57(6):325-327.

Although the separable fastener, marketed as the zipper, has become a necessary component of modern life, its convenience comes at a price: its attack upon the penis. Nearly 2000 US males sustain a zipper-related penis injury (ZIRPI) annually, and many of these accidents require emergency surgery. Nevertheless, the zipper has been tolerated quietly for 100 years on account of its unsurpassed ease of use.

A 2013 study in which data were extrapolated from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) showed that an estimated 17,616 patients presented to emergency departments with ZIRPI in the United States between 2002 and 2010.1 In this landmark research, the authors found that zippers are the most common cause of penile injury among men and are a close second to toilet seats among boys. Prior to this study’s publication, the literature on ZIRPI largely consisted of anecdotes or isolated case series from various medical centers.

Zippers and ZIRPI: A Historical Look

ZIRPI has a storied history in popular culture, having been featured in media such as the 1998 film There’s Something About Mary, in which a high school boy (played by Ben Stiller) misses his chance to go to the prom with his dream date (played by Cameron Diaz) because he gets his penis stuck in his zipper. In fact, most urologists and emergency medicine clinicians have seen at least one ZIRPI case during their career. One would think that such a public health menace would be the focus of great controversy, yet the zipper has been tolerated quietly for almost 100 years—why so?

It was not always this way. After its invention, the zipper was persistently ridiculed, as evidenced by Aldous Huxley’s treatment of it in his classic 1932 novel, Brave New World. Huxley’s futuristic work, set in the 26th century, is alarming in its anticipation of potential changes to come, describing a world where humans are genetically bred to fill 1 of 5 castes, where Jesus has been supplanted by Henry Ford, and where people fasten their clothing with, of all things, zippers! Huxley wrote that in the year 632 af (after Ford), John the Savage gazes wistfully upon the nymphomaniac Lenina, noting that “The zippers on Lenina’s spare pair of viscose velveteen shorts were at first a puzzle, then solved, a delight. Zip, and then zip; zip, and then zip; he was enchanted.”2

Later on, John the Savage has an encounter with one of the Controllers, who explains why great literature and the Bible must be kept locked up2:

“God isn’t compatible with machinery and scientific medicine and universal happiness. You must make your choice. Our civilization has chosen machinery and medicine and happiness. That’s why I have to keep these books locked up in the safe. They’re smut. People would be shocked if …”

The Savage interrupted him. “But isn’t it natural to feel there’s a God?”

“You might as well ask if it’s natural to do up one’s trousers with zippers,” said the Controller sarcastically.

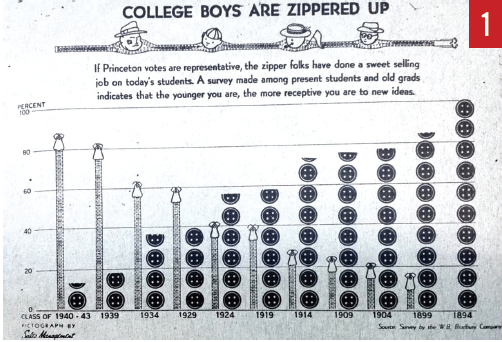

Why this sarcasm? Perhaps, as with many new inventions, there is a tendency for the older generations to pooh-pooh the latest newfangled device as unnecessary. For example, a 1940 poll of Princeton University students and alumni showed that acceptance of the new zippered fly was inversely related to age, with members of the older classes clearly favoring buttoned flies, and recent graduates and students tending toward the new zippers (Figure 1).3

Figure 1. Results of a 1940 survey done at Princeton University’s annual class reunions showed a definite trend in sartorial preference depending on graduates’ ages.

Likewise, the military was also slow to accept the device, fearing that zippers could not be repaired in the field. Tailors thought the zipper too expensive to sew into clothing, and in fact, for the first 15 years of their existence, zippers were relegated to tobacco pouches or boots, where they got their start.

Originally, the zipper had been developed as a variation of the “clasp locker,” a boot-lacing device invented in the late 1890s by urban planner Whitcomb Judson in his spare time, in order to aid older people who were just a little too corpulent to bend over easily and lace their boots by hand.4 After Judson and his partner, Lewis Walker, started the Hookless Fastener Company in New Jersey in the last decade of the 19th century, they hired an ambitious Swedish American electrical engineer named Gideon Sundback, who made significant improvements to the clasp locker and therefore was awarded the patent for the “separable fastener” in 1917 (Figure 2).4

Figure 2. The original patent for the “separable fastener,” designed by Gideon Sundback.

Nevertheless, it was Bertram Work, president of the B.F. Goodrich Company in Akron, Ohio, who had the brilliance to market the device on his company’s rubber galoshes using the onomatopoetic name “zipper,” and the name stuck—in fact, to this day, the athletic teams at the University of Akron are known as the Zips.

By the time members of the British royalty began wearing zippered trousers in the late 1930s, the “Battle of the Fly” (fought in the fashion magazines) was dominated by the zipper, even after a safer alternative, Velcro, was invented just 2 decades later. The zipper was easy to use and could be operated with one hand, and it also encouraged children to be self-reliant, because they could now dress themselves with the use of this new simple machine.

By the 1930s, the zipper’s founding fathers had moved their enterprise further westward, to Meadville, Pennsylvania, where they appreciated the benefits of a dedicated workforce and easy transportation lines to the expanding nation. Meanwhile, the risks of the new device were being debated at the highest levels of the corporation. Executives at the renamed Talon Inc., which was then the largest manufacturer of zippers in the world, circulated memos questioning the safety of the device being used so close to the genitalia: “Retailers were made to worry that they could be held legally liable if a man injured himself with the newfangled machine on his trouser fly. Stories were circulated about particularly embarrassing failures of zippers, and these acquired lives of their own. Only the most conscientious salesmanship, involving much follow-up work and educational activity, could overcome obstacles like these.”4

ZIRPI: A Modern-day Concern

The first case of a ZIRPI was reported more than 80 years ago in the Journal of the American Medical Association,5 but the zipper’s great popularity silenced the naysayers. Subsequent studies have shown that the risk factors for ZIRPI include being uncircumcised or insufficiently circumcised.6 Interestingly, “going commando,” or sans underwear, is not a clear risk factor for ZIRPI, as studies are conflicting6-8; hence, this is currently a hot topic in ZIRPI research. It could be that men who dress “commando” are more careful zipping their fly!

Generally, ZIRPI may be successfully managed by lubricating the entrapped skin9 or by cutting either the zipper slider or teeth.10,11 A backup procedure involves “popping” the inner and outer faceplates of the slider by inserting a small screwdriver from the side and twisting it 90°,12 but in some cases, an emergency circumcision may be necessary to liberate the penis.

A careful visual assessment of the genitalia is the first step in successful management of cases of ZIRPI. Most patients are uncircumcised, and the meatus is usually uninvolved; however, catheterization should be avoided unless the patient is in urinary retention, and even then not until after urologic evaluation, if there is any question of urethral injury.

The nonsurgical options for penile liberation mentioned above should be individualized based on the patient’s age and stress level, as well as the ZIRPI treatment experience of the emergency department personnel. Often, the best option is emergency urologic consultation and anesthesia.

For example, a 63-year-old man checked into our emergency department last year complaining of a “penis problem.” He would not be more explicit about the problem until he was triaged to an acute-care bed, where he revealed his situation. On physical examination, he was a slightly disheveled, uncircumcised elderly man, dressed “commando,” who had cut away his zipper where it had engaged his foreskin (Figure 3). After conservative measures to free the foreskin failed, a urologist was consulted, and the patient was taken to the operating room for an emergency circumcision.

Figure 3. A patient’s zipper-entrapped penis before emergency circumcision (left; note the YKK moniker on the slider handle) and after the procedure (right).

However, for most patients, who are fortunate enough to be freed of their zippers without surgery, appropriate intervention still includes arranging prompt urologic follow-up for infection prophylaxis, as well as possible elective circumcision to prevent recurrence. Wearing underwear is certainly a good idea for a number of reasons, but it has not been scientifically proven to prevent ZIRPI, and this subject will require future prospective studies. Health care personnel should also be aware that ZIRPI patients of all ages may be somewhat ashamed of their predicament and should reassure them that their accident is not unique.

One would think that the US Consumer Product Safety Commission, which oversees NEISS, would have something to say about these incidents of ZIRPI; however, most product liability or recalls involving zippers relate to instances of choking or asphyxiation occurring from zippered outerwear or from bean bag chairs. In contrast, ZIRPI litigation is widely viewed by most experts in the legal and medical fields alike to be frivolous, hearkening to the controversial case of a plaintiff who was awarded a multimillion-dollar settlement after she spilled hot coffee on her lap at a restaurant drive-through.13 As one legal expert writes,14 “Another every-day object, men’s pants with zippers, is responsible for thousands of emergency-room visits for zipper-related penis injuries … . Manufacturers know this or, at least, should know this because of the press coverage of the fact. … But pants do not require zippers to close. … One can argue that both pants manufacturers and coffee vendors should be liable for injuries caused when people injure themselves; that’s bad public policy that most people will instinctively reject, but it’s at least intellectually honest.”

Perhaps the best explanation for the zipper’s success is its ability to expose the penis rapidly for critical functions, including micturition. Its most successful advocate may have been Tadao Yoshida (1908-1993), the dynamic Japanese businessman who started YKK, a Tokyo-based zipper-manufacturing company that survived World War II to eventually drive Talon and similar competitors out of the marketplace and provide most of the zippers in the universe (yes, one of their accounts is NASA). Although Yoshida is not well-known outside of the business community, if you are wearing a zippered item right now, there is a very good chance that your zipper slider handle bears a YKK imprint.

Lawrence M. Wyner, MD, is a professor in the Division of Urology in the Department of Surgery at the Marshall University Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine in Huntington, West Virginia.

REFERENCES:

- Bagga HS, Tasian GE, McGeady J, et al. Zip-related genital injury. BJU Int. 2013;112(2):E191-E194.

- Huxley A. Brave New World. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1968.

- Talon Inc. College boys are zippered up. Sales Management. October 20, 1940:33.

- Friedel R. Zipper: An Exploration in Novelty. New York, NY: WW Norton & Co; 1994.

- Susskind MV. Zipper trauma. JAMA. 1936;107(10):809.

- Yip A, Ng SK, Wong WC, Li MK, Lam KH. Injury to the prepuce. Br J Urol. 1989;63(5):535-538.

- Nolan JF, Stillwell TJ, Sands JP Jr. Acute management of the zipper-entrapped penis. J Emerg Med. 1990;8(3):305-307.

- Wyatt JP, Scobie WG. The management of penile zip entrapment in children. Injury. 1994;25(1):59-60.

- Kanegaye JT, Schonfeld N. Penile zipper entrapment: a simple and less threatening approach using mineral oil. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1993;9(2):90-91.

- Nakagawa T, Toguri AG. Penile zipper injury. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15(4):303-304.

- Inoue N, Crook SC, Yamamoto LG. Comparing 2 methods of emergent zipper release. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(4):480-482.

- Raveenthiran V. Releasing of zipper-entrapped foreskin: a novel nonsurgical technique. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(7):463-464.

- Liebeck v McDonald’s Restaurants, 1995 WL 360309 (NM Dist Ct).

- Frank T. Zippers, penis injuries, and McDonald’s hot coffee redux. PointofLaw.com. http://www.pointoflaw.com/archives/2013/04/zippers-penis-injuries-and-mcdonalds-hot-coffee-redux.php. Published April 24, 2013. Accessed May 11, 2017.