Peanut-Induced Anaphylaxis

A 4-month-old boy with history of atopic dermatitis was brought to the emergency department with difficulty breathing and 4 episodes of nonmucous, nonbloody vomiting. These symptoms had occurred 30 minutes after the boy’s mother for the first time had fed him porridge made with peanut butter. Before that, the boy had been breastfed exclusively.

On physical examination, the patient was tachypneic (respiratory rate, 50 breaths/min) with intercostal retractions and moderate wheezing that progressed to stridor and sweating. A hypopigmented patch also was noted over the flexor surface of the boy’s arm. The mother denied any family history of asthma or food allergy. She also denied fever, cough, changes in bowel or bladder habits, or rash in the boy.

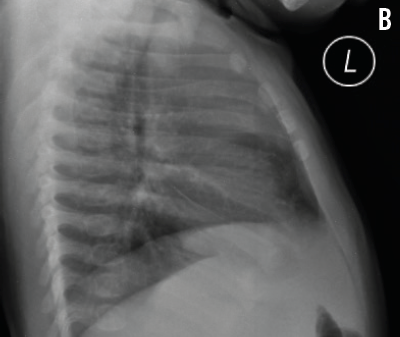

Laboratory tests showed a negative respiratory syncytial virus panel result and a finger-stick glucose level of 185 mg/dL. Results of a complete blood count were as follows: white blood cell count, 8,500/µL; hemoglobin, 9.9 g/dL; hematocrit, 29.4%; platelet count, 336 × 103/µL; neutrophils, 29.3%; and lymphocytes, 43.8%. Chest radiographs showed slight bronchial wall thickening as may be seen with viral infection or reactive airway disease. No focal pneumonia was identified (A and B).

Chest radiograph showing slight bronchial wall thickening as may be seen with viral infection or reactive airway disease.

The patient continued to be tachypneic despite receiving 3 albuterol nebulizations, so he was admitted to the pediatric floor for respiratory support and further management.

On arrival to the pediatric floor, the patient’s respiratory rate trended downward to 36 breaths/min. On physical examination, the lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. He presented with no retractions, wheezes, or stridor. His respiratory symptoms resolved approximately 9 hours after they had appeared. He was discharged in less than 24 hours; the mother received an epinephrine pen (0.15 mg/0.3 mL) and instructions to avoid peanuts in both the child’s diet and her own.

The boy was referred to the allergy clinic. Radioallergosorbent test results showed high immunoglobulin E (IgE) level (943 µg/L) with a strong class 6 reaction to peanuts, codfish, and egg whites. The mother was advised to reintroduce all foods into her diet except for peanuts, and also to avoid tree nuts, fish, and seafood while breastfeeding. It was recommended that all other family members avoid peanuts, as well.

At his 12-month follow-up visit, the boy’s growth and development were normal. Complete elimination of peanut-containing products from his diet avoided further respiratory distress. An epinephrine pen dose of 0.15 mg was prescribed, this time for the mother and for the babysitter to keep on hand.

An estimated 5.1% of children younger than 17 years of age were affected by food allergies from 2009 to 2011. Food allergy is an immune-mediated adverse reaction to foods characterized by symptoms affecting the skin, the gastrointestinal system, and/or the respiratory system and ranging from mild to severe, including life-threatening anaphylaxis. These reactions can be IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated processes. Symptoms of IgE-mediated food allergy start within minutes to 1 hour (and rarely more than 2 hours) after contact with the allergen.

Lateral radiograph of the boy’s chest on which no focal pneumonia was identified.

Although any food allergen can trigger anaphylaxis, peanuts and tree nuts trigger the majority of severe food reactions. Up to 30% of fatal anaphylaxis cases are triggered by food allergens. More than 90% of food-triggered anaphylaxis fatalities in the United States are associated with exposure to peanuts or tree nuts. In one report, more than half of fatal anaphylaxis cases were triggered by nuts. In a recent study of children with food allergy in the United States, anaphylaxis most often was associated with multiple food allergies or having allergies to peanuts, tree nuts, or shellfish.

Infants who are breastfed exclusively can show signs and symptoms of food allergies. This is thought to be a result of maternal dietary macromolecules that are absorbed in the gut and transmitted to the infant via human milk. Cow’s milk, egg, wheat, and peanut allergens have been detected in human milk. Atopic dermatitis, as seen in our patient, is the most common dermatologic manifestation occurring during the breastfeeding period and occasionally is caused by food allergies.

Anaphylaxis likely is underdiagnosed in infants, and food-induced anaphylactic reactions have been reported in infants as early as 1 month of age. Respiratory symptoms and anaphylaxis have been reported even in exclusively breastfed infants owing to occult ingestion of allergens from foods in the mother’s diet, such as cow’s milk and fish.

Although the timing of the onset of anaphylaxis can range from seconds to a few hours after exposure to the causal food allergen, the majority of such reactions manifest within 1 hour of exposure. Most reactions are uniphasic, with symptoms resolving quickly after treatment. Up to 20% of reactions are biphasic, in which recurrence of symptoms is seen after resolution of the initial symptoms without reexposure to the allergen. The biphasic response can vary in severity and most often occurs within 8 hours of the initial symptoms.

In some cases, the first presenting sign of food allergy is anaphylaxis. It is important to remember that the severity of allergic reactions to foods cannot be predicted by history or by either skin prick testing or allergen-specific IgE testing.

The diagnosis of food allergy in a breastfed infant requires a detailed history and the recognition of the signs and symptoms of food allergy. Disappearance of symptoms in an infant with maternal avoidance of trigger foods and reappearance with reintroduction of trigger foods to the mother’s diet is diagnostic of food allergy. The history should include questions about comorbid medical problems, prior experiences with the triggering food, and a history of anaphylaxis.

Epinephrine, administered intramuscularly in the thigh, is the treatment of choice for anaphylaxis. For children who weigh less than 10 kg (our patient weighed approximately 6 kg), the provider and family should weigh the risks associated with a delay in dosing or with dosing errors when using an ampule, syringe, or needle against the risks of using a non-ideal auto-injector. For patients with a history of a life-threatening reaction, the prescription of an auto-injector is preferred.

Parents should be advised that following epinephrine administration, they should immediately call 911 for transport to the nearest hospital for further medical management and observation for biphasic anaphylaxis. Because as many as 20% of children with food-induced anaphylaxis require 2 doses of epinephrine to adequately treat symptoms, parents should have 2 doses available at all times. Administration of a second dose of epinephrine is indicated when the first dose leads to no improvement, or when symptoms recur or worsen in the 5 to 10 minutes immediately following the first dose. n