Peer Reviewed

Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome

Author:

Omar Hasan, DO

Swedish Covenant Hospital, Chicago, Illinois

Citation:

Hasan O. Osmotic demyelination syndrome. Consultant. 2017;57(8):509-510.

A 31-year-old man with a past medical history of alcohol abuse presented with sudden-onset ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, and bilateral resting hand tremors that had started approximately 1 week prior. The symptoms had started with bilateral hand tremors and had progressed such that he was unable to type and work at his computer. Shortly thereafter, the patient noticed difficulty speaking and walking. He stated that he was unable to articulate coherently while having telephone conversations. He noted difficulty with balance while walking and a sensation of weakness in both lower extremities. These symptoms had progressed over a week, at which point the patient presented to the emergency department (ED).

History. The patient denied illicit drug use, and he did not take any medications. His past surgical history and family history were unremarkable. He reported that he had drunk alcohol daily for the past 10 years, and that he had stopped cold turkey about 4 weeks prior. Further investigation revealed that the patient had presented to the ED 3 weeks prior for an episode of loss of consciousness with associated nausea, vomiting, and bilateral hand tremors. At that time, the patient had reportedly attempted to quit drinking and had not consumed alcohol for 2 to 3 days before arrival. Findings of a head computed tomography (CT) scan performed at that visit were unremarkable. He was hyponatremic (sodium, 111 mEq/L) and hypochloremic (chloride, 89 mEq/L). His potassium level was mildly elevated at 5.8 mEq/L, and his bicarbonate level was 15 mEq/L. His blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels were elevated at 41 mg/dL and 1.4 mg/dL, respectively. His magnesium level was low at 1.4 mg/dL. His albumin level was low at 2.9 g/dL.

During this prior ED visit, the patient received an intravenous bolus of 1 L of normal saline. He received another bolus of 1 L overnight and was placed on a maintenance regimen of 83 mL/h of normal saline. The patient was monitored for alcohol withdrawal based on the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol protocol. His hyponatremia was overcorrected with normal saline; his sodium level increased to 131 mEq/L within approximately 24 hours. At that time, the patient had no neurological symptoms other than bilateral hand tremors, which were attributed to alcohol withdrawal. He signed himself out of the hospital against medical advice the next day.

Physical examination. Physical examination at the current ED visit, 2 weeks after the episode of hyponatremia, revealed abnormal neurological findings of resting hand tremors, dysarthria, and abnormal finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin test results. He also had a positive Romberg sign and decreased sensation but no focal weakness in the upper and lower extremities.

Diagnostic tests. Laboratory test results were consistent with macrocytic anemia and hyponatremia, with a serum sodium level of 133 mEq/L. The levels of other electrolytes, the international normalized ratio, and renal function test results were within normal limits.

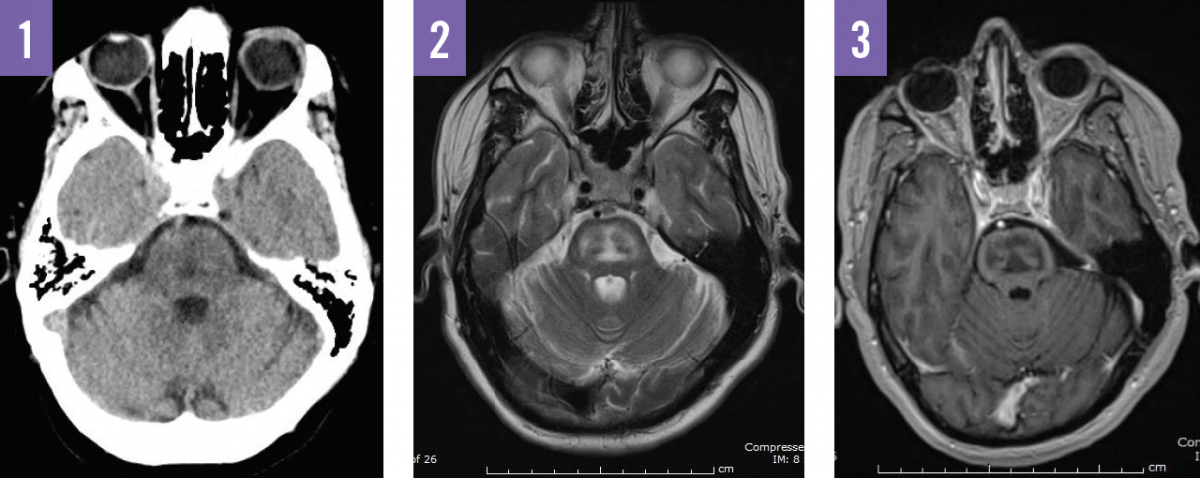

Findings of an initial CT scan of the head were abnormal, with areas of low attenuation concerning for demyelination (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed an abnormal hyperintensity on T2-weighted scans involving the central pons but mostly sparing the cortical spinal tracts (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1, CT image showing areas of low attenuation representing demyelination of the central tracts. Figure 2, T2-weighted MRI image showing hyperintense white matter tracts with peripheral sparing, classic for ODS. Figure 3, contrast MRI image showing no enhancement, a typical finding in ODS.

Based on the patient’s history, presentation, and diagnostic test results, he received a diagnosis of osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS).

Discussion. ODS is a rare neurological disorder associated with conditions that cause severe serum osmolar electrolyte disturbances, whereby neurons in the central nervous system undergo noninflammatory demyelination.1 Affected neurons are often isolated to the pons, referred to more specifically as central pontine myelinolysis (CPM). However, extrapontine neurons of the midbrain, thalamus, and basal ganglia are also stripped of the myelin sheath (extrapontine myelinolysis [EPM]); hence the term ODS is used to describe both CPM and EPM.2

Risk factors include liver disease, hypokalemia, malnutrition, and alcoholism. CPM was first documented as a syndrome affecting malnourished persons with alcoholism, resulting in pseudobulbar palsy and flaccid quadraparesis.3 The majority of patients (50.5%) with a radiologically confirmed diagnosis of ODS have a history of alcohol abuse.1

The exact pathophysiology of ODS is not understood. One hypothesis suggests that a reduced serum osmolality triggers neurons to adapt by reducing intracellular organic solute concentrations to avoid cellular edema.1,4 When serum osmolality is corrected, the neurons cannot replenish organic solute concentrations at an equal rate, and the cells shrink and subsequently demyelinate. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that chronic severe hyponatremia (serum sodium < 120 mEq/L) with a rapid correction is the strongest predicting factor and is found in approximately 56% of cases.1

The clinical presentation of ODS is heterogeneous, making detection challenging. Global encephalopathy of varying degrees is seen, from subclinical to coma and death. Specific signs and symptoms may include altered mental status, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, tremor, quadraparesis, parkinsonism, and dystonia.1,2,4 The onset of neurological disturbance ranges considerably but is usually 7 to 14 days following an episode of osmotic derangement.4 Prognosis was once thought to be dismal, although it is now recognized that many patients have favorable outcomes, even when presenting with severe neurological function.1,2,5,6

Our patient made an excellent recovery during his hospital stay, to independence within 3 days with daily physical and occupational therapy, which has been commonly reported in cases of ODS in patients with alcoholism.7 He then signed himself out against medical advice and was lost to follow-up.

The incidence of ODS is not known. Greater access to MRI has aided in diagnosing mild and subclinical cases.6,7 The gold standard for diagnosis of ODS is MRI.6,8 Lesions often demonstrate contrast enhancement on conventional T2-weighted imaging and restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging.6,8 However, MRI findings do not seem to correlate with the clinical severity nor predict prognosis.6,8 The only evidence-based treatment for ODS is supportive measures.9

REFERENCES:

- Singh TD, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(12):1443-1450.

- Sajith J, Ditchfield A, Katifi HA. Extrapontine myelinolysis presenting as acute parkinsonism. BMC Neurol. 2006;6:33.

- Adams RD, Victor M, Mancall EL. Central pontine myelinolysis: a hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1959;81(2):154-172.

- Yoon B, Shim Y-S, Chung S-W. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis after alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43(6):647-649.

- Louis G, Megarbane B, Lavoué S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients hospitalized in intensive care units with central or extrapontine myelinolysis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):970-972.

- Graff-Radford J, Fugate JE, Kaufmann TJ, Mandrekar JN, Rabinstein AA. Clinical and radiologic correlations of central pontine myelinolysis syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(11):1063-1067

- Odier C, Nguyen DK, Panisset M. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: from epileptic and other manifestations to cognitive prognosis. J Neurol. 2010;257(7):1176-1180.

- Förster A, Nölte I, Wenz H, et al. Value of diffusion-weighted imaging in central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Neuroradiology. 2013;55(1):49-56.

- Deleu D, Salim K, Mesraoua B, El Siddig A, Al Hail H, Hanssens Y. “Man-in-the-barrel” syndrome as delayed manifestation of extrapontine and central pontine myelinolysis: beneficial effect of intravenous immunoglobulin. J Neurol Sci. 2005;237(1-2):103-106.