Peer Reviewed

A Farmer’s Thumb Lesion After a Sheep Bite: Identifying the Zoonosis

Authors:

Eiyu Matsumoto, MB; Sarah L. Miller, MD; Marthe N. Dika, MD; Nkanyezi N. Ferguson, MD; Andrew J. Holte; and Jennifer R. Carlson, PA-C

Citation:

Matsumoto E, Miller SL, Dika MN, Ferguson NN, Holte AJ, Carlson JR. A farmer’s thumb lesion after a sheep bite: identifying the zoonosis. Consultant. 2017;57(10):609.

A previously healthy 38-year-old farmer presented to the emergency department (ED) with a lesion on his left thumb. The patient stated that he had first noticed bumps on his left thumb 3 weeks ago. The lesions had grown, eventually coalescing into a large nodule. The lesion initially had been tender but had gradually become painless. A physician had prescribed a 2-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, which had led to no improvement. A second physician had attempted incision of the lesion, but there had been no drainage.

At this visit, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. Physical examination of his left thumb revealed a 4-cm, brown to violaceous nodule with surrounding erythema (Figure). Upon questioning about his exposure history, the patient noted that the lesion had developed in the wound bed where his daughter’s sheep had recently bitten him. The patient added that the sheep had had a scab around his mouth.

Answer on next page

Answer: Orf Virus Infection

Figure 1: A 4-cm, brown to violaceous nodule with surrounding erythema was present on the patient’s left thumb.

A previously healthy 38-year-old farmer presented to the emergency department (ED) with a lesion on his left thumb. The patient stated that he had first noticed bumps on his left thumb 3 weeks ago. The lesions had grown, eventually coalescing into a large nodule. The lesion initially had been tender but had gradually become painless. A physician had prescribed a 2-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, which had led to no improvement. A second physician had attempted incision of the lesion, but there had been no drainage.

At this visit, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. Physical examination of his left thumb revealed a 4-cm, brown to violaceous nodule with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). Upon questioning about his exposure history, the patient noted that the lesion had developed in the wound bed where his daughter’s sheep had recently bitten him. The patient added that the sheep had had a scab around his mouth.

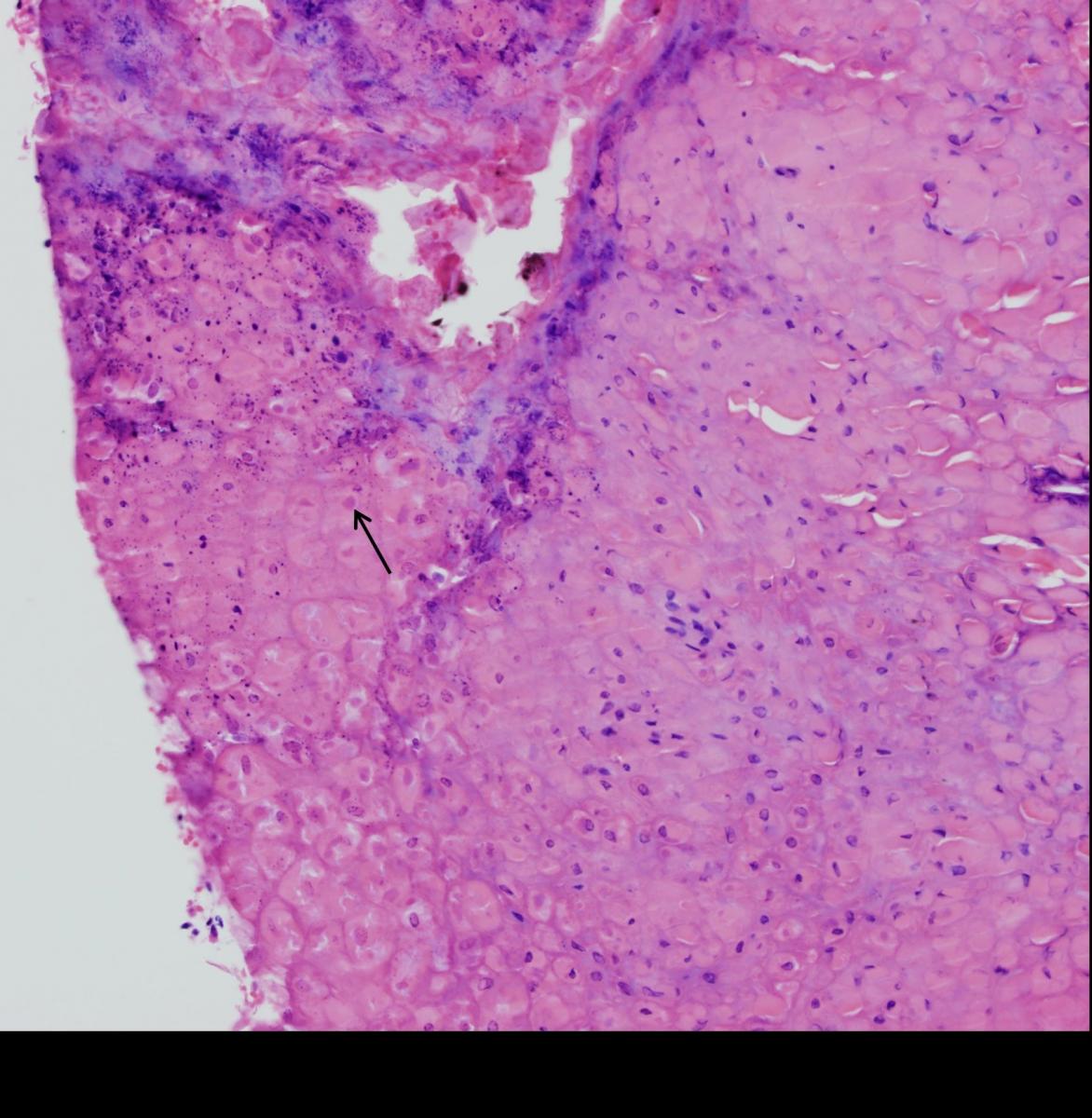

Based on the man’s clinical presentation and exposure history, the likely diagnosis was orf virus infection. However, to rule out other etiologies, a punch biopsy was performed for hematoxylin-eosin staining, and sterile tissue cultures were obtained. Histologic test results showed epidermal acanthosis and necrosis with cytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions, consistent with orf virus infection (Figure 2). Tissue cultures were negative for pathogenic organisms. The patient was reassured, and the lesion eventually resolved spontaneously without sequelae.

Figure 2: Histologic test results showed epidermal acanthosis and necrosis with cytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions (arrow), consistent with orf virus infection.

Discussion

Orf virus is a zoonotic member of the genus Parapoxvirus. Parapoxviruses are found worldwide and are common pathogens in small ruminants such as sheep and goats.1 Parapoxvirus infection in sheep and goats may be referred to as sore mouth, scabby mouth, contagious pustular dermatitis, contagious ecthyma, or orf,2 and the corresponding human infection is referred to as orf. Human infection, characterized by localized epithelial lesions, is an occupational hazard for persons who handle infected animals, including farm workers, abattoir workers, and veterinarians.1

The orf virus is easily transmissible to humans via direct contact with the mucous membranes of infected animals. Human infection occurs via cuts and scratches, often on the hands with a single lesion. Very rare instances of human-to-human transmission have been reported, resulting from direct contact with lesions or with fomites that contacted both lesions and broken skin; nosocomial transmission was responsible for an outbreak of disseminated orf among patients in a hospital burn unit in Turkey.3,4

Orf lesions are produced by hypertrophy and proliferation of epidermal cells. Histologic examination findings of human lesions show epidermal necrosis, many small multilocular vesicles, mixed inflammatory infiltrate, and intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion bodies.1,5

Clinically, after 3 to 5 days of incubation, lesions begin as erythematous macules and then raise to form papules (days 7-14), sometimes with a targetoid appearance. Lesions become nodular or vesicular and often ulcerate after 14 to 21 days. Complete healing can take 4 to 6 weeks.6

The diagnosis is made based on exposure history, the presence of a characteristic lesion, and laboratory test results. Although orf virus infection is self-limiting in persons with normal immune systems, it can resemble the skin lesions associated with potentially life-threatening zoonotic infections such as tularemia, cutaneous anthrax, and erysipeloid. Therefore, rapid and definitive diagnosis is critical. Tularemia is associated with exposure to rabbits or sylvan rodents, whereas erysipeloid is associated with exposure to swine.1

Human orf virus infection and naturally acquired anthrax both can result from exposure to sheep and goats, and a history of animal contact exposure alone is insufficient to identify the etiology of a lesion, and laboratory testing is required.1

Among the histopathologic (but nonpathognomonic) features of orf virus infection are intraepithelial ballooning and intracytoplasmic inclusions. While negative-stain electron microscopy findings and serologic test results can confirm parapoxvirus infection, they cannot distinguish orf virus from other Parapoxvirus virus species such as the paravaccinia (pseudocowpox) virus; only polymerase chain reaction can definitively identify a parapoxvirus as orf virus.1

In most cases, the disease is self-limited, and treatment is nonspecific. Lesions generally heal without complications. The use of topical cidofovir cream, 3%, has demonstrated apparent beneficial effects in anecdotal reports; however, no data from controlled trials are available.7 Immunocompromised patients can have progressive, destructive lesions requiring medical interventions such as antiviral therapy and surgical debridement.1 Immune response is maintained only for a limited time, and 8% to 12% of individuals experience a recurrence of orf infection.6

Although orf virus infection is generally benign, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes potentially life-threatening conditions. Accurate and prompt diagnosis is facilitated by obtaining a complete history and by maintaining a high index of suspicion for orf in cases of an unusual lesion in a person exposed to farm animals.

LISTEN TO OUR PODCAST WITH THE LEAD AUTHOR HERE.

Eiyu Matsumoto, MB, is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City, Iowa.

Sarah L. Miller, MD, is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City, Iowa.

Marthe N. Dika, MD, is a resident physician in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City, Iowa.

Andrew J. Holte is a student at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City, Iowa.

Nkanyezi N. Ferguson, MD, is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City, Iowa.

Jennifer R. Carlson, PA-C, is a physician assistant at the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Iowa City, Iowa.

REFERENCES:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Orf virus infection in humans—New York, Illinois, California, and Tennessee, 2004-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(3):65-68.

- Scott PR. Overview of contagious ecthyma (orf, contagious pustular dermatitis, sore mouth). Merck Veterinary Manual. http://www.merckvetmanual.com/integumentary-system/contagious-ecthyma/overview-of-contagious-ecthyma. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- Turk BG, Senturk B, Dereli T, Yaman B. A rare human-to-human transmission of orf. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(1):e63-e65.

- Midilli K, Erkılıç A, Kuşkucu M, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of disseminated orf infection in a burn unit, Gaziantep, Turkey, October to December 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(11):20425.

- Zimmerman JL. Orf. JAMA. 1991;266(4):476.

- Petersen BW, Damon IK. Other poxviruses that infect humans: parapoxviruses (including orf virus), molluscum contagiosum, and yatapoxviruses. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol 2. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:1703-1706.

- McCabe D, Weston B, Storch G. Treatment of orf poxvirus lesion with cidofovir cream. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(11):1027-1028.