Essentials of Dermatology For The Primary Care Provider

ABSTRACT: Skin diseases are among the most frequently encountered conditions in primary care. This series reviews the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical characteristics of the more common dermatologic conditions, and offers tips for differentiating among them. The management approach for each cutaneous condition is discussed, including topical and systemic medical therapies and which cases warrant consideration of a systemic workup. This first part will focus on facial dermatitides and common generalized eruptions.

Skin concerns, from rashes to bumps, can trouble patients and perplex practitioners. As many as 1 in 3 patients presenting to their primary care doctor have at least 1 skin problem.1 This article reviews common dermatologic diseases, with a focus on differentiating entities and detailing treatment options for multiple conditions to help guide practitioners through the world of cutaneous disease. Note: Many of the treatments discussed in the article are not FDA approved for the indication used and represent off-label use.

Facial Dermatitides

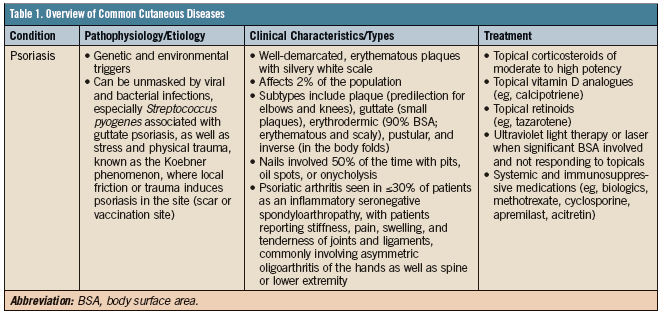

Patients frequently present to the primary care provider with complaints of facial eruptions, which are more worrisome to patients due to the high visibility. Table 1 delineates common skin diseases, several of which are reviewed in greater detail below.

Figure 1. Grade III acne vulgaris mixture of inflammatory papules/pustules and comedones. This patient would require a combination of treatment, with oral antibiotic and topical retinoids plus a benzoyl peroxide.

Acne Vulgaris

Acne vulgaris is a common disorder of the pilosebaceous unit resulting from obstruction of the follicular orifice, increased sebum production, overgrowth of Propionibacterium acnes bacteria, and inflammation (Figure 1). The condition affects nearly 85% of adolescents and continues into adulthood for many.2 Pathophysiology, clinical appearance, and treatment options are reviewed in Table 1.

It is important for clinicians to gather a thorough history. In particular, remember to ask female patients whether lesions worsen during menstruation, as this may occur in 40% of women.3 Ruling out underlying triggers also is key. Medications that can worsen acne include corticosteroids, progestins, lithium, phenytoin, and iodides. Endocrine abnormalities also can contribute to acne, especially if acne is abrupt or early in onset. Generally, mild acne does not require systemic therapy; however, moderate to severe acne cases often necessitate both topical and oral therapy.

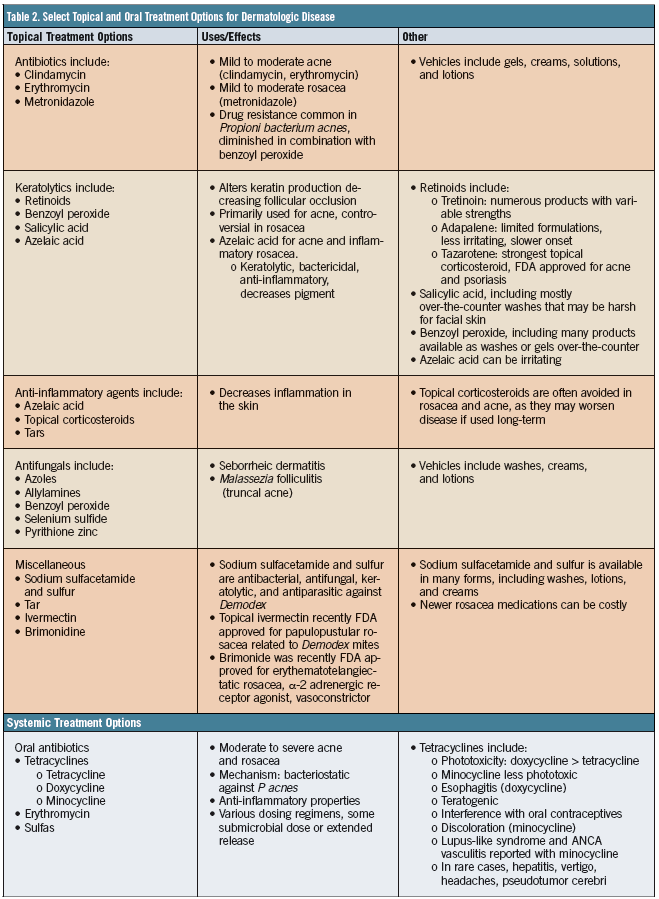

Tables 1 and 2 detail treatment options for acne and facial eruptions in more depth. Before beginning any treatment, a practitioner should discuss pregnancy prevention with female patients, as many of the topical and oral treatments (eg, tetracyclines) are contraindicated during pregnancy or lactation. Additionally, all treatments take 6 to 12 weeks for improvement; thus, patients should be warned that acne often worsens before it improves.

Figure 2. Rosacea, papular pustular subtype; the patient may benefit from topical azelaic acid with topical metronidazole or topical ivermectin. A low-dose oral antibiotic, like doxycycline, also might be effective in reducing the number of lesions and flares.

Rosacea

Rosacea is facial condition characterized by recurrent episodes of flushing, erythema, papules, pustules, and telangiectasias (Figure 2). The etiology of rosacea is unknown; however, there are several prevailing theories and clinical subtypes,4 which are further described in Table 1. It is important to ask patients about flushing and blushing, as well as symptoms of burning and irritation of the skin or eyes—clues to an underlying diagnosis of rosacea.

Although a benign condition, rosacea often diminishes a patient’s quality of life, resulting in low self-esteem and embarrassment.5

A variety of topical and systemic treatments for rosacea are effective; however, patient education and routine skin care are key pillars of therapy. Moisturizers are particularly important in preventing transepidermal water loss and in restoring the skin barrier to reduce exacerbations. Sunscreen, especially physical blockers such as zinc oxide or titanium dioxide, help decrease inflammatory molecules and block production of reactive oxygen species.6

In addition to the mainstays of treatment, such as oral or topical antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents described in Table 2, several products designed to treat rosacea have gained recent approval from the FDA. Brimonidine tartrate, 0.5%, is a topical α-adrenergic receptor agonist that reduces persistent facial erythema through vasoconstriction for 6 to 7 hours after application. Ivermectin cream, 1%, is effective in the treatment of inflammatory papular or pustular rosacea, and in studies it has been proven superior to metronidazole cream, 0.75%, a current cornerstone of rosacea treatment.7 Though costly, both newer medications can be helpful in select rosacea patients as part of a combination approach.6

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis frequently affects adults, favoring the scalp, ears, face, central chest, and intertriginous areas. The etiology is likely related to active sebaceous glands with reaction to the Malassezia (formerly known as Pityrosporum) yeast, Malassezia furfur, part of the resident flora of the skin. Patients demonstrate sharply demarcated red, brown, or pink, greasy, scaly patches or plaques. Tables 1 and 2 describe treatment options. The course is chronic and relapsing, which can necessitate periodic interval use of topical antifungal shampoos and creams. Rarely, oral antifungals such as fluconazole or itraconazole are required. For refractory cases, patients should be referred to a dermatologist for management.8

Eyelid Dermatitis

Patients frequently present with eyelid dermatitis, which may occur secondary to a number of underlying diseases, including irritant dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea with blepharitis, or allergic contact dermatitis.

Because distinguishing the etiology can be problematic, practitioners should gather a thorough history, including the following: asking questions regarding the use of soaps, shampoos, makeup, hair dyes, or moisturizers to assess for irritant or allergic components; collecting information about an atopic personal or family history; making queries about dandruff elsewhere; and investigating the cosmetics on the hands and nails that frequently contact the eyes and can incite allergic reactions.

Studies examining the cause of eyelid dermatitis have found that allergic contact dermatitis is most common, accounting for nearly 30% to 70% of cases, followed by atopic dermatitis in more than 10% of patients, and, less frequently, irritant dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis.9 The history and examination may warrant patch testing, where common chemicals that can cause contact dermatitis are applied to a patient’s back to see if he or she reacts. Allergy testing also may be beneficial.

Common treatments, regardless of the underlying cause, include: cool wet compresses followed by the application of petroleum jelly; topical corticosteroids of class 5 to 7 in ointment form, which harbor fewer preservatives and provide more hydration; discontinuation of certain products, including makeup and cleansers; and avoidance of preservatives or fragrances. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are recommended in a variety of eyelid dermatitides, given that they do not thin or lighten the skin in the way a corticosteroid may over time.9

Figure 3. Chronic hand dermatitis in an adult patient with a history of atopic dermatitis. Treatment would include ultra-potent topical corticosteroids, avoidance of irritants (like water or chemicals), and liberal use of emollients.

Common Generalized Eruptions

Eczema

The term eczema encompasses a heterogeneous group of inflammatory skin disorders that share similar hallmarks of epidermal inflammation. It includes such entities as atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, dyshidrotic eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, and asteatotic eczema. Eczema can present acutely, characterized by red, weeping, draining skin with blisters, or it can present chronically, with dry, thickened, scaly skin with alteration of pigment, appearing either at times hyperpigmented or depigmented. Frequent etiologies include extrinsic causes, such as irritant dermatitis or allergic contact dermatitis, or intrinsic causes, such as atopic or dyshidrotic eczema. Common morphologic types include hand eczema, nummular eczema (coin-shaped lesions), stasis dermatitis (often affecting the lower extremities in the setting of vascular insufficiency), and atopic dermatitis, which often begins in infancy as part of the “atopic” diathesis.

Atopic dermatitis is one of the more common inflammatory skin conditions. In children, it is characterized by involvement of the cheeks, scalp, and extensor aspects of the extremities. Initially, it appears as weeping, erythematous papules and plaques, sometimes accompanied by vesicles and crusting. Over time, lesions become chronic with thickened, lichenified plaques; later in adults, it presents as chronic hand or face dermatitis (Figure 3). Pruritus is a constant complaint regardless of the patient’s age.10

Asteatotic eczema, or “winter’s itch,” which commonly occurs in the elderly, presents with dry, rough, scaly patches and plaques with superficial cracking of the skin that appears like a “dried riverbed.” Areas usually involved are the shins, lower flanks, and posterior axillary line. Elimination of aggravating factors, such as frequent bathing, and application of emollients help significantly.

Stasis dermatitis, another form of eczema, often is associated with other signs of venous hypertension, as evidenced by pitting edema and hemosiderin deposition in the skin. Eventually, patients may develop erythema and scaling around the medial malleoli with intense pruritus and subsequent excoriations; later stages may show cutaneous ulcerations. Due to trials of various home remedies, patients often experience contact sensitization, which complicates the clinical appearance, causing acute flares of vesiculation and weeping that overlie more chronic, lichenified plaques. This contact sensitization may lead to a generalized eczematous eruption on other parts of the body, known as autosensitization. It is important that practitioners understand and recognize this phenomenon in a patient with a generalized eczematous eruption in the background of secondarily infected or flared stasis dermatitis. Gaining control of the original area of eczema will often lead to improvement in the rest of the body.

For the various types of eczema, therapeutic principles are similar; the dictum, “If it is wet, dry it; if it is dry, wet it,” applies. Drying agents include water and aluminum acetate, and “wetting” agents comprise emollients, such as ointments and creams. Topical therapies for various forms of eczema encompass corticosteroids as well as immunosuppressives such as the calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream). Systemic therapy is rarely necessary; however, in refractory or generalized cases, prescribed treatments include oral prednisone, phototherapy, or other immunosuppressives such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil. In cases of superinfection, evidenced by weeping, purulent, or honey-crusted plaques overlying areas of eczema, antibiotics may help.

The most significant component of any treatment, however, is educating the patient about the chronic, relapsing nature of eczema. Patients must understand that treatments are tools, not cures. Several proactive measures can help prevent flares: Patients should avoid triggers, modify wet work or handwashing, and liberally use emollients such as ointments and creams, especially after contact with water. Bathing should be brief; showers should be taken with lukewarm to cooler water; moisturizing soaps should be applied primarily to body folds and soiled areas; and within several minutes of bathing, patients should freely administer creams or ointments.11

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common, chronic, immune-mediated skin disease that affects nearly 2% of the population in the United States. Patients often harbor a polygenic predisposition combined with certain environmental triggers. Clinically, lesions demonstrate sharply demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaques and occasional pustules (Figure 4). Several forms of psoriasis exist, as described in Table 1.

Figure 4. Silvery, white scale overlying the erythematous plaque on the leg in a patient with psoriasis. Treatment would initially entail topical corticosteroids with the possibility of ultraviolet light therapy or systemic agents if the patient fails to respond to extensive topical treatment.

Psoriatic arthritis can be found in 5% to 30% of psoriasis patients, appearing most commonly as asymmetric oligoarthritis of the small joints of the hands and feet.12 Recently, studies have shown that patients with psoriasis also have a higher risk of heart disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and renal disease.13,14 Patients with more severe and chronic psoriasis have significant inflammation in not only the skin but also the vascular tree, liver, joints, and tendons, which raises the risk for atherosclerosis and endothelial cell injury.15 Providers should therefore encourage all patients with psoriasis to modify controllable risk factors for cardiovascular and renal disease.

Most patients with psoriasis have mild disease treatable with topical medications. Corticosteroids, which possess anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, immunosuppressive, and vasoconstrictive effects, are first line in treating psoriasis. Vitamin D analogues, such as calcipotriene, which inhibit keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, also are effective. Additionally, topical retinoids such as tazarotene can normalize abnormal keratinocyte differentiation and diminish inflammatory markers. In patients with more severe disease, phototherapy with ultraviolet light, or systemic immunosuppressives such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, should be considered. Oral retinoids are an option in select patients, though side effects limit the use of many of these systemic medications.

Recently, biologic therapies have altered the traditional landscape of treatment and are routinely administered as first-line agents in advanced, resistant, or widespread psoriasis, especially if phototherapy is not feasible or fails to cause improvement. Biologic agents belong to several classes, primarily tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and interleukin inhibitors, specifically interleukin 12/23 and interleukin 17A. For biologic agents, patients must be screened for tuberculosis at baseline and during treatment. Most monitoring guidelines suggest regular chemistry screens with liver function tests, complete blood counts, a hepatitis panel, and an HIV panel prior to treatment, with close attention to infections and cancer development during therapy.16

The second part of this series will focus on the use of topical corticosteroids as well as common cutaenous infections and systemic diseases. n

References:

- Lowell BA, Froelich CW, Federman DG, Kirsner RS. Dermatology in primary care: prevalence and patient disposition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(2):250-255.

- Knutsen-Larson S, Dawson AL, Dunnick CA, Dellavalle RP. Acne vulgaris: pathogenesis, treatment, and needs assessment. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(1):99-106.

- Bershad SV. In the clinic. Acne. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(1):

- ITC1-1-ITC1-16.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, Hata TR. Rosacea: part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(5):749-758.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard grading system for rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(6);907-912.

- van Zuuren EJ, Gupta AK, Gover MD, Graber M, Hollis S. Systematic review of rosacea treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):107-115.

- Taieb A, Ortonne JP, Ruzicka T, et al; Ivermectin Phase III study group. Superiority of ivermectin 1% cream over metronidazole 0.75% cream in treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea: a randomized, investigator-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(4):1103-1110.

- Pedrosa AF, Lisboa C, Gonçalves-Rodrigues A. Malassezia infections: a medical conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):170-176.

- Wolf R, Orion E, Tüzün Y. Periorbital (eyelid) dermatides. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(1):131-140.