Peer Reviewed

A Deeper Look at a Woman’s Persistent Hip Pain Uncovers a Case of Osteomyelitis

AUTHORS:

Eric Maher, DO; Bernadette Pendergraph, MD; and Yasser Giron, MD

CITATION:

Maher E, Pendergraph B, Giron Y. A deeper look at a woman’s persistent hip pain uncovers a case of osteomyelitis. Consultant. 2016;56(9, Suppl):S17-S18.

A 49-year-old woman with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and hypertension presented with chronic right hip and leg pain.

History. She had undergone surgery for a right thigh abscess and subsequent wide excision and drainage for necrotizing fasciitis 2 years prior to presentation. At that time, wound cultures were positive for Candida albicans and Escherichia coli. She reported that although the wound had completely healed, she still had persistent difficulty walking, standing, and transitioning due to pain and weakness in her right hip. These symptoms had progressed, and she had been in a wheelchair with decreasing use of a walker since her surgery.

Physical examination. The patient appeared in no acute distress, was seated in her wheelchair, and appeared pale. Her vital signs were significant for hypotension, with a systolic blood pressure in the 60s mm Hg. Cardiovascular examination findings were significant for tachycardia. The lungs were clear to auscultation, and abdominal examination findings were benign.

Musculoskeletal and neurologic examination findings were significant for right hip flexion strength, 3+/5; left hip flexion, 4/5; right knee extension, 4/5; left knee extension/flexion, 4+/5; right knee flexion, 4/5; and bilateral dorsiflexion/plantar flexion, 4+/5. Sensation was intact and symmetric in the woman’s lower extremities. In addition, there was an approximately 4-cm shortening of the right medial malleolus compared with the left, with atrophy of the right thigh muscles.

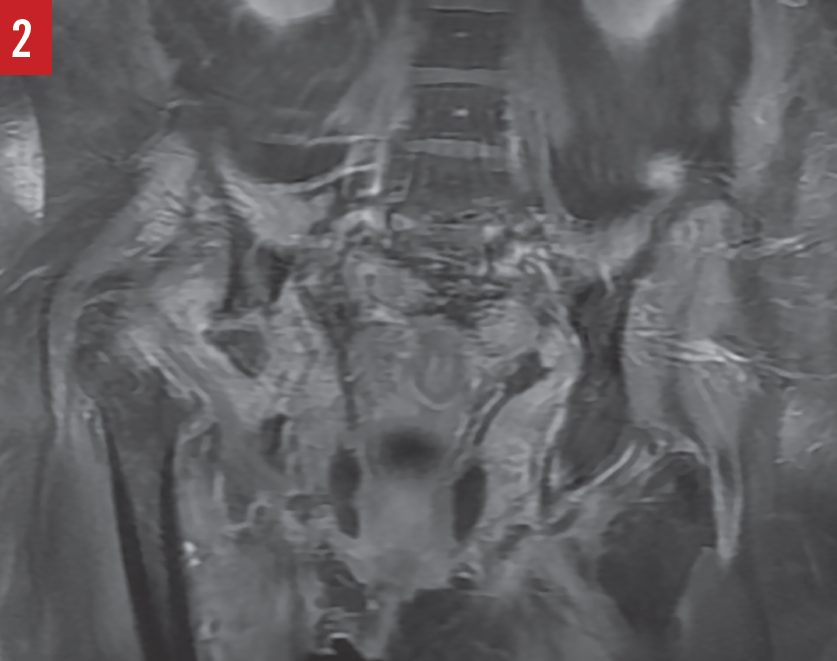

Diagnostic tests. Results of a complete blood cell count included an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 15,800/µL with a predominance of neutrophils, and a hemoglobin level of 10.3 g/dL. Urinalysis was positive (3+) for leukocyte esterase, negative for nitrite, and positive (4+) for bacteria, with greater than 182 WBCs per high-power field. Subsequent urine culture results were negative for pathogens. An anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis (Figure 1) and a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the pelvis (Figure 2) showed the absence of the right femoral head and acetabulum.

Based on these findings, the patient received a diagnosis of osteomyelitis.

Discussion. Osteomyelitis is a rare complication of skin and soft tissue infections. In our case, the patient’s risk of developing osteomyelitis was related to her poorly controlled diabetes and her history of polymicrobial necrotizing fasciitis. The inciting event leading to osteomyelitis in our patient most likely was direct or contiguous inoculation from adjacent soft tissue infection and subsequent surgical intervention.1

Studies have demonstrated progression to osteomyelitis in approximately 33% of stage 4 ulcers2 and 26% of nonhealing ulcers.3 Patients with vascular compromise, such as in diabetes mellitus, are predisposed to osteomyelitis due to an insufficient local tissue response.4

Less likely in our patient was hematogenous osteomyelitis of a long bone, where infection occurs at the metaphysis due to the vascular loops just before the epiphyseal plate.1 This is typically a chronic condition with nonspecific symptoms. In cases of direct inoculation (contiguous focus osteomyelitis), clinical manifestations are more localized than those of hematogenous osteomyelitis and typically involve multiple organisms.5 Our patient’s initial presentation 2 years prior for necrotizing fasciitis was that of an acute infection, with wound cultures demonstrating a polymicrobial infection. After surgery, her acute infection had resolved, with temporary improvement in pain and right hip function. However, symptoms of pain and decreased range of motion returned slowly as the infection spread insidiously and infected bone. Clinical markers for her deteriorating condition were the progression of right hip pain and decreasing mobility.

Changes in ambulatory function are important symptoms that should lead all health care providers to investigate the reason for a patient’s needing to use assistive devices, including wheelchairs. In the case presented here, it had been presumed that the patient needed a wheelchair as a result of postoperative deconditioning, and it was not until the constellation of hypotension, tachycardia, and worsening pain developed that her osteomyelitis was identified. When patients require medical equipment to assist with mobility or activities of daily living, it is important to evaluate the joint or limb involved and perform a functional assessment that includes assessment of a stable base of support, the ability to transfer weight from one limb to the other, and alternating body weight transfer as the body moves forward.6 Ultimately, deconditioning should be a diagnosis of exclusion while further workup is performed and assistance with physical therapy is offered.

Outcome of the case. Based on her initial presentation and the urinalysis findings that were concerning for infection, the patient initially was started on ceftriaxone for possible pyelonephritis leading to septic shock. Based on the subsequent radiographic evidence of chronic osteomyelitis, she was transitioned to oral ciprofloxacin for 7 days on discharge.

On a subsequent admission for non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, MRI scans demonstrated findings consistent with chronic osteomyelitis. She was then treated with intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for a total of 6 weeks. Serial measurements of serum inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or C-reactive protein level) may be useful in monitoring for resolution and recurrence of osteomyelitis; however, if these test results have not normalized by the end of the planned treatment course, further clinical and/or radiographic investigation is warranted.7

This patient awaits further evaluation by orthopedic surgery specialists for total hip arthroplasty.

Eric Maher, DO, is a sports medicine fellow at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, California, and a physician with Team to Win West Coast Sports Medicine Foundation in Manhattan Beach, California.

Bernadette Pendergraph, MD, is program director of the Sports Medicine Fellowship at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, California.

Yasser Giron, MD, is a family physician at Southern California Permanente Medical Group in Santa Ana, California.

References:

- Calhoun JH, Manring MM. Adult osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19(4):765-786.

- Allman RM. Pressure ulcers among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(13):850-853.

- Moss RJ, La Puma J. The ethics of pressure sore prevention and treatment in the elderly: a practical approach. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(9):905-908.

- Paluska SA. Osteomyelitis. Clin Fam Pract. 2004;6(1):127-156.

- King RW. Osteomyelitis in emergency medicine. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/785020-overview. Updated June 15, 2016. Accessed August 16, 2016.

- Gouelle A. Use of Functional Ambulation Performance Score as measurement of gait ability: review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(5):665-674.

- Trampuz A, Zimmerli W. Diagnosis and treatment of infections associated with fracture-fixation devices. Injury. 2006;37(suppl 2):S59-S66.