Counseling Patients on the Use of Intranasal Steroids in Allergic Rhinitis Management

Authors:

Gabriel Ortiz, MPAS, PA-C, and Mary Knudtson, DNSc, NP

Citation:

Ortiz G, Knudtson M. Counseling patients on the use of intranasal steroids in allergic rhinitis management. Consultant. 2017;57(6):328-334.

ABSTRACT: Allergic rhinitis is a major health burden that affects millions of individuals and interferes with quality of life and daily functioning. Intranasal steroids (INS) are the gold standard of rhinitis therapy due to their well-established efficacy and safety profiles when used as recommended. Despite the potential benefits, barriers related to patient perceptions of INS and incorrect administration technique may hinder initiation of, adherence to, and/or correct use of these agents. Patient education and counseling on the use of INS where appropriate is key to improving rhinitis outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Allergic rhinitis, intranasal steroids

Allergic rhinitis is one of the most common chronic conditions in the United States.1-3 It affects 30 million to 60 million US people annually,1,4,5 or 10% to 30% of adults and up to 40% of children.4

Rhinitis is often undiagnosed and/or undertreated.6-9 The symptoms are sometimes dismissed as a nuisance because they may resemble those of the common cold.3,10 However, the potential impact on quality of life (QoL), productivity, and daily functioning is substantial.4,7,11-14 For example, rhinitis is associated with sleep disturbance, headache, cognitive impairment, and fatigue in adults.4,6,15 In children with rhinitis, undertreatment may lead to frequent absence from school, behavioral difficulties, and worsening of comorbidities such as asthma.6,11,14,16 Absenteeism, limitation of daily activities, and loss of productivity attributed to rhinitis are higher than those attributed to other prevalent conditions such as type 2 diabetes and hypertension.17

The most bothersome allergy symptoms are nasal congestion and red, itchy eyes.1,6,7,11,12 Nasal congestion has a notable impact on QoL, disrupting productivity, sleep, and daily functioning.6,7,11 In primary care practice, patients frequently present with symptoms of nasal congestion and sneezing, request medications to relieve their symptoms, and/or have self-diagnosed their rhinitis.3

DIAGNOSIS

Health care providers (HCPs) in primary care frequently encounter individuals with rhinitis and play a major role in its diagnosis and management.18,19 Knowledge of local information related to rhinitis (eg, types of airborne allergens or pollen counts in the region) may facilitate diagnosis.3 Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of rhinitis have been developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation,16 the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology joint task force,4 and the Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma guideline panel.10,20

Allergic rhinitis is diagnosed based on patient history, physical examination findings, skin allergy test results, and/or immunoglobulin E (IgE) test results.4,10,16 A presumptive diagnosis can be made when the patient’s history and physical examination findings strongly suggest an allergic cause and at least 1 of the 4 hallmark symptoms of rhinitis are present: runny nose, itchy nose, congestion, or sneezing.16 The physical examination and history should focus on the nose and other organs that are likely affected by allergies (eg, throat, lungs, eyes).4

Skin tests and IgE-specific blood tests (ie, immunoassays) are recommended to confirm a clinical diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in patients who have persistent symptoms despite medical management, allergen avoidance, or environmental controls, or when identification of the allergen is needed for more targeted pharmacologic therapy or immunotherapy.4,16 The allergens selected for skin testing should be based on patient-specific factors, including medical history, environment, age, occupation, geographic area of residence, and activities.4 In most cases, skin testing is preferred over immunoassays and other in vitro testing methods for determining specific IgE antibodies due to superior simplicity, speed, cost savings, and sensitivity.4 Radiographic imaging is discouraged for the diagnosis of rhinitis because of the lack of supporting evidence, the potential for adverse events (AEs), and unnecessary cost.4,16

MANAGEMENT OF RHINITIS

HCPs may consider various treatment strategies (Figure 1) depending on the clinical scenario encountered (ie, rhinitis symptom type/severity, patient preference regarding treatment).16 Two basic strategies are allergen avoidance and environmental control measures.10,16 Patients are advised to avoid exposure to allergens that trigger rhinitis—the most common of which include pet dander, pollen, dust mites, and mold—and to use multifaceted patient-managed interventions such as air filtration systems, dehumidifiers, impermeable bed covers, and acaricides.4,10,16,20 For a patient who prefers complementary medicine, some guidelines include acupuncture as an option that HCPs can offer, although additional evidence from well-designed studies is needed before clear recommendations for or against this approach can be made.16 Decisions regarding pharmacotherapy should be guided by the type of rhinitis (eg, allergic rhinitis alone, combined allergic and nonallergic rhinitis, episodic rhinitis), the most bothersome symptoms, severity, disease duration, patient preference, patient age,10,16 and medication characteristics (eg, efficacy, availability, cost).4,10

Intranasal steroids. Intranasal steroids (INS) are the first-line treatment for management of rhinitis and are the most effective class of medication for symptom relief.4,20,21 As a mainstay of rhinitis pharmacotherapy for adults and children, INS are recommended for patients with symptoms that are persistent or affect their QoL.16,21 Their efficacy in controlling the 4 major symptoms of rhinitis (ie, nasal congestion, sneezing, nasal itching, and rhinorrhea), particularly in severe rhinitis, is widely accepted; some INS are indicated for or may also provide relief from ocular symptoms (eg, itchy, watery eyes).4,16,22-26

INS have well-established efficacy and tolerability profiles and superiority over other treatment options.4,10,16,20 Their effectiveness in treating rhinitis is attributed to direct action on pathologic inflammatory pathways.16,27 Although INS are administered topically, one of the most frequent concerns among patients and clinicians is the possibility of systemic exposure and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression, which is a known AE associated with oral steroids.18 In reality, suppression of the HPA axis and other clinically significant AEs are rare when INS are taken at the recommended doses because of their limited systemic bioavailability.10,18

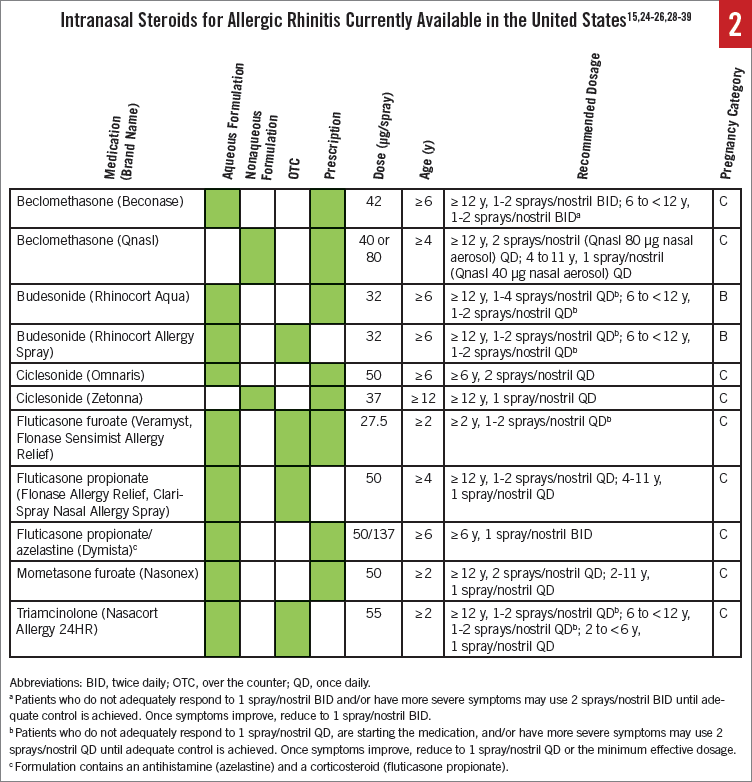

The currently available INS are comparable in their overall clinical response.4 Several INS sprays are available in the United States (Figure 2).15,24-26,28-39 Four have been granted over-the-counter (OTC) status by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)40: Nasacort Allergy 24HR (triamcinolone acetonide)37 in 2013, Flonase Allergy Relief (fluticasone propionate)24 in 2014, Rhinocort Allergy Spray (budesonide)35 in 2015, and, most recently, Flonase Sensimist Allergy Relief (fluticasone furoate)38 in 2016. Additional brands also have become available following the initial switches of these agents (eg, ClariSpray Nasal Allergy Spray [fluticasone propionate]39). All INS are available as aqueous spray solutions, except for ciclesonide and beclomethasone dipropionate, which are nasal aerosols.22,26,28,41

Oral steroids. Oral steroids are not recommended as first-line therapy for rhinitis and should be avoided in children and patients who are pregnant or who have contraindications.10,20 Long-term use of oral steroids has been associated with significant suppression of the HPA axis.42 In children, the potent growth inhibition observed with oral steroids has raised concern.5,18,42 Other safety signals, such as a potentially greater risk of osteoporosis and fractures in adults, have also been noted with oral steroids.42 Interindividual variability in response further limits the utility of oral steroids.4 In rare instances, a short course of oral steroids (≥ 7 days) may be considered as a last resort in patients with moderate to severe nasal and/or ocular symptoms when other therapies have failed.4,20 Intramuscular steroids are strongly discouraged in the management of rhinitis due to the potential for AEs that are more serious than the symptoms of rhinitis.10,20

Second-generation oral antihistamines. Although not as effective as an INS, oral second-generation, nonsedating antihistamines can be recommended for rhinitis, particularly when sneezing and itching are the most bothersome symptoms.4,10,16,20 Oral antihistamines have a fast onset of action, making them more effective than other agents for the treatment of intermittent symptoms, and they may be less costly in generic form compared with INS.4,16 They also may be effective in reducing allergic conjunctivitis but are minimally effective for nasal congestion4,10 and less effective for treating severe rhinitis compared with other agents.4

Intranasal antihistamines. Like oral antihistamines, IN antihistamines also have a rapid onset of action.4 However, IN antihistamines are less effective than INS for the treatment of nasal symptoms4 and are less strongly recommended compared with oral second-generation antihistamines because of patient preference for oral formulations and taste aversion, which is a common AE associated with IN formulations.16,20 IN antihistamines may be useful in seasonal rhinitis4,16 but are not recommended for persistent rhinitis pending additional evidence to support their relative safety and efficacy.20

Other agents. Oral decongestants may be useful on an as-needed basis; they are not recommended for regular use as either monotherapy or in combination, because their potential for AEs outweighs the modest reduction in symptoms that they provide.10,20 Oral leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) are not recommended as primary therapy for patients with rhinitis but can be considered for patients who cannot tolerate IN therapy, are concerned about sedation, or have both rhinitis and asthma.16

Combination therapy. When monotherapy fails to adequately control rhinitis symptoms, combination therapy can be considered.4,16 IN antihistamines are the most effective add-on treatment when INS monotherapy has failed.16 However, the use of oral antihistamines as an add-on treatment to INS provides minimal benefit.16 Combined therapy with an antihistamine and LTRA has inferior efficacy compared with INS4,43 and is not recommended.16 IN oxymetazoline is an effective add-on to INS for severe nasal obstruction, but the duration of use is limited because of the risk of rhinitis medicamentosa (ie, rebound nasal congestion) or worsening of congestion.10,16

Immunotherapy. Allergen-specific immunotherapy is a third major strategy in rhinitis management4,10,44 and is the only treatment with potential to change the natural history of rhinitis.16 Referral to an allergist or immunologist should be considered when there is inadequate symptom control, a decrease in QoL or ability to perform daily activities, an inability to tolerate medication AEs, a need to identify causative allergens and receive guidance on environmental control, the presence of comorbidities (eg, asthma, chronic sinusitis), or a possibility that allergen immunotherapy will be needed.4 Confirmation of the presence of specific IgE antibodies to causative antigens is required before initiating allergen-specific immunotherapy.4,10,16

ROLE OF THE PRIMARY CARE PROVIDER

Primary care providers play a vital role in overseeing the management of patients with allergic rhinitis. To accomplish this task, they must understand the recommended treatment approaches for rhinitis (both prescription and OTC), be able to implement them, and know when to refer patients to specialists. Primary care providers are essential to the initiation of allergen immunotherapy, since they must identify candidates, articulate the risks and benefits of treatment to patients, and/or refer them to a clinician who can administer that type of therapy.16

Patients’ unfamiliarity with risks and benefits and their lack of knowledge about proper use of INS are major barriers to the effective treatment of rhinitis symptoms.45 Patient counseling/education is important in overcoming these barriers and improving treatment adherence.4,46 It is especially important that clinicians educate patients on the benefits of medication (eg, improved QoL with better symptom control), since rhinitis is sometimes misdiagnosed (eg, as a prolonged common cold), and its associated burden is frequently trivialized compared with other chronic conditions.3,43,46

Individualization of treatment strategies, continuation past the initial visit, and inclusion of the caregiver or advocate are essential to providing the best care possible.4,10 The causes of poor adherence—eg, false expectations, concerns about the safety of the therapy, previous or potential side effects, cost/lack of access1,47—should be addressed through patient education to promote adherence.48 For patients who are self-managing their allergic rhinitis symptoms with OTC medications, it will be important to monitor these issues during routine office visits and provide counseling as necessary.

ADDRESSING BARRIERS TO The USE OF INS

Fear of systemic AEs associated with the use of INS. Steroid phobia and reluctance to use INS are prevalent: A survey of 170 patients with rhinitis revealed that 48% were concerned about AEs, including systemic effects.47 Some HCPs may also harbor a fear of systemic AEs from INS. However, at the recommended doses, INS are not generally associated with clinically significant systemic AEs.4,49 FDA approval for use in patients as young as 2 years has been granted for some INS.25,30,37 The most common AEs associated with these agents relate to local irritation (eg, dryness, burning, stinging, blood-tinged secretions, epistaxis).4,16,25,30,37

Fear of growth inhibition. Because oral corticosteroids have well-known, potent growth-inhibiting effects,5,18,42,50 some patients and clinicians may be concerned about these effects with the use of INS.5,18,51 Studies conducted with more-sophisticated techniques to measure growth have found a reassuring lack of growth effects with some newer-generation, lower-bioavailability inhaled steroids in children with asthma52; however, recent studies using similarly robust study designs and methods (per FDA guidance) have found evidence of small but statistically significant effects on 1-year growth velocity (0.27-0.45 cm/y reduction vs placebo) in children with persistent allergic rhinitis using INS daily for 12 months.51-54 The clinical relevance of these findings is not known, since there are no long-term (ie, ≥ 1 year) clinical data evaluating the effect of INS use during childhood on final adult height using these more robust designs.52,53 Judicious use of INS with a careful assessment of benefits relative to risks is warranted52; routine growth monitoring and use of the lowest effective dosage are recommended for pediatric patients.25

Fear of negative effects on bone. The clinical data investigating the effects of INS on bone are limited,4,55 and multiple confounding factors, including underlying disease, previous exposure to oral steroids, genetics, and physical activity, make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.56 However, from the available published evidence, INS have not been associated with significant changes in biochemical markers of bone metabolism or bone mineral density.57,58

Additional patient concerns. Medication class warnings suggest that the development of glaucoma or increased ocular pressure may result from the use of INS.51 Patients with glaucoma, cataracts, or other eye problems should have their eyes checked regularly, since increased intraocular pressure following the use of INS has been reported.31,59 Fears regarding addiction, weakened resistance to infection, and cancer development with INS use were reported in a survey of 170 patients with rhinitis,47 but these associations are not supported elsewhere in the literature. Patient education should address such concerns and provide assurance that the most common AEs associated with INS relate to local irritation and may include mild bleeding of the septum, which sometimes results from improper technique.5,16 Patients who find that their INS is too drying, causes headaches, or has an unpleasant smell or taste should be made aware that multiple INS are available to suit a wide variety of preferences.16,49

Establishing realistic expectations regarding efficacy. The onset of symptom control with INS often is not immediate, usually occurring within 12 hours, although it may begin as early as 3 to 4 hours in some patients.4 It is therefore important to set realistic expectations during patient education/counseling on these agents. Patients should be instructed that INS are most effective when they are used every day.24

Ensuring correct administration technique. All medications approved for reclassification from prescription status to OTC status must meet FDA criteria that the patient alone can self-administer without harm, and the intended uses, directions, and warnings must be understandable for consumers. However, previous data with prescription INS products suggested the possibility that patients could benefit from additional education on appropriate technique. For example, one study reported that 56% of patients were unable to demonstrate correct administration of their specific INS; among these, 47.6% failed to clear the nose, 14.3% did not shake the bottle, 6.3% did not fully depress the spray pump, and 4.8% failed to either position the tip correctly or alternate nostrils.46

Directions for use as described in the package insert vary among the INS.15,25,26,28,29,31-33,36 In general, the following steps are recommended5: (1) hold the head in a neutral, upright position; (2) blow the nose to clear it; (3) insert the spray tip into the nostril; (4) aim the spray tip to the side, away from the middle of the nose (nasal septum); (5) activate the device as directed; (6) gently sniff and breathe in while spraying; and (7) exhale through the mouth. These steps should be repeated as necessary to administer the recommended number of sprays. Cleaning the spray tip/cap is recommended in the product labeling of some INS. Correct technique and avoidance of sniffing too strongly will help prevent drip from the nose or down the back of the throat, both of which may affect adherence.46

Adherence to the recommended dosing regimen. Once patients agree to use INS, primary care providers often face the challenge of persuading them to remain adherent to the treatment regimen (eg, daily use instead of intermittently or as needed). The recommended duration of use will vary for prescription products relative to OTC products, so it will be important to provide individualized dosing instructions for the selected treatment. Patients are often reluctant to take a medication routinely and would rather take it on an as-needed basis. This failure to adhere to the recommended treatment schedule contributes directly to patient outcomes observed in clinical practice.46 Some patients attribute poor adherence to forgetfulness, with one study reporting that 78% of patients forgot to use their INS medication up to 5 times.46

Patients also should be educated about the potential risks of chronic overdosage with INS. Overall, INS are a strongly recommended rhinitis treatment given their established safety profile and the preponderance of benefit over harm.16 However, if INS were used at higher than recommended dosages, systemic effects (eg, hypercorticism, adrenal suppression) could occur.31,59

The switch to OTC status for these agents in the United States is relatively recent, and there are currently no published reports of overuse of OTC INS. Because overuse of other OTC allergy products has been reported previously,60 it is prudent to instruct patients about the importance of adherence to the recommended dosing schedule and for them to contact their clinician for guidance if symptoms are not adequately managed with their INS when used as directed.

Patient preference. Patient preferences (eg, regarding smell, taste, throat rundown, nose runout, feel of the spray in the nose and throat, ease/comfort of use, delivery device, monetary cost), perceptions, and beliefs are important factors in treatment initiation, adherence, and satisfaction.61-63 Some of the reasons for a lack of adherence to pharmacotherapy, such as the medication running down the back of the throat, may be attributed to incorrect administration technique, which can be resolved through patient education.

CONCLUSIONS

Rhinitis is a common condition that affects millions of individuals but is often trivialized or underdiagnosed. Although it is associated with a substantial impact on QoL and daily functioning,4,7,12-14 accurate diagnosis and timely, effective treatment can lessen the burden of disease.18,64 Of the many treatment options that are available, INS are the mainstay of rhinitis therapy, with well-established efficacy and a favorable safety profile when used as recommended. However, a variety of patient barriers, including steroid phobia and incorrect administration technique, may lead to suboptimal patient outcomes. Primary care providers are well positioned to educate and help patients overcome these barriers and promote proper use of INS.

Gabriel Ortiz, MPAS, PA-C, is a PA at BreatheAmerica of El Paso, Texas. He is the former American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) liaison to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the former AAPA liaison to the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee. He is the current AAPA liaison to the NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Coordinating Committee for Prevention of Peanut Allergy.

Mary Knudtson, DNSc, NP, is Executive Director of Student Health Services at the University of California Santa Cruz in Santa Cruz, California.

Disclosures: Gabriel Ortiz is a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Meda, Mylan, and Teva, and is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Meda, Mylan, Quest Diagnostics, Teva, and Thermo Fisher. Mary Knudtson has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This article was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare. Medical writing assistance was provided by Barbara Zeman, PhD, and Diane Sloan, PharmD, of Peloton Advantage and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare. GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare provided a full review of the article.

REFERENCES:

- Allergies in America: A Landmark Survey of Nasal Allergy Sufferers. Executive Summary: Adult. New York, NY: Schulman, Ronca and Bucuvalas Inc; 2006. http://www.worldallergy.org/UserFiles/file/Allergies%20in%20America%20(AIA)%20-%20Adult%20Executive%20Summary.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- Khan DA. Allergic rhinitis and asthma: epidemiology and common pathophysiology. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35(5):357-361.

- Ryan D, Van Weel C, Bousquet J, et al. Primary care: the cornerstone of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2008;63(8):981-989.

- Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2 suppl):S1-S84.

- Benninger MS, Hadley JA, Osguthorpe JD, et al. Techniques of intranasal steroid use. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(1):5-24.

- Stewart MG. Identification and management of undiagnosed and undertreated allergic rhinitis in adults and children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(5):751-760.

- Shedden A. Impact of nasal congestion on quality of life and work productivity in allergic rhinitis: findings from a large online survey. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4(6):439-446.

- Nathan RA, Meltzer EO, Derebery J, et al. The prevalence of nasal symptoms attributed to allergies in the United States: findings from the burden of rhinitis in an America survey. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29(6):600-608.

- Spinozzi F, Murgia N, Baldacci S, et al; ARGA Study Group. Characteristics and predictors of allergic rhinitis undertreatment in primary care. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29(1):129-136.

- Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008. Allergy. 2008;63(suppl 86):8-160.

- Thompson A, Sardana N, Craig TJ. Sleep impairment and daytime sleepiness in patients with allergic rhinitis: the role of congestion and inflammation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(6):446-451.

- Bielory L, Skoner DP, Blaiss MS, et al. Ocular and nasal allergy symptom burden in America: the Allergies, Immunotherapy, and RhinoconjunctivitiS (AIRS) surveys. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35(3):211-218.

- Canonica GW, Mullol J, Pradalier A, Didier A. Patient perceptions of allergic rhinitis and quality of life: findings from a survey conducted in Europe and the United States. World Allergy Organ J. 2008;1(9):138-144.

- Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Jennifer DM, et al. Burden of allergic rhinitis: results from the Pediatric Allergies in America survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(3 suppl):S43-S70.

- Dymista [package insert]. Somerset, NJ: Meda Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2015.

- Seidman MD, Gurgel RK, Lin SY, et al. Clinical practice guideline: allergic rhinitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(1 suppl):S1-S43.

- de la Hoz Caballer B, Rodriguez M, Fraj J, Cerecedo I, Antolín-Amérigo D, Colás C. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on work productivity in primary care practice and a comparison with other common diseases: the Cross-sectional study to evAluate work Productivity in allergic Rhinitis compared with other common dIseases (CAPRI) study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26(5):390-394.

- Hayden ML, Womack CR. Caring for patients with allergic rhinitis. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19(6):290-298.

- Angier E, Willington J, Scadding G , Holmes S, Walker S. Management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis: a primary care summary of the BSACI guideline. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;19(3):217-222.

- Brożek JL, Bousquet J, Baena-Cagnani CE, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines: 2010 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(3):466-476.

- Sur DKC, Plesa ML. Treatment of allergic rhinitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(11):985-992.

- van Bavel JH, Ratner PH, Amar NJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily treatment with beclomethasone dipropionate nasal aerosol in subjects with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33(5):386-396.

- Jacobs R, Martin B, Hampel F, Toler W, Ellsworth A, Philpot E. Effectiveness of fluticasone furoate 110 µg once daily in the treatment of nasal and ocular symptoms of seasonal allergic rhinitis in adults and adolescents sensitized to mountain cedar pollen. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(6):1393-1401.

- Flonase Allergy Relief [product label]. US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/205434Orig1s000Lbl.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- Veramyst [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

- Zetonna [package insert]. Marlborough, MA: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2014.

- Nielsen LP, Dahl R. Comparison of intranasal corticosteroids and antihistamines in allergic rhinitis: a review of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Respir Med. 2003;2(1):55-65.

- Qnasl [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Teva Respiratory LLC; 2014.

- Nasacort AQ [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis US LLC; 2013.

- Nasonex [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co Inc; 2013.

- Flonase [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2015.

- Rhinocort Aqua [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca; 2010.

- Beconase AQ [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2015.

- Blaiss MS. Safety update regarding intranasal corticosteroids for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(6):413-418.

- Children’s Rhinocort Allergy Spray [product label]. US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/020746Orig1s034lbl.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- Omnaris [package insert]. Marlborough, MA: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2013.

- Nasacort Allergy 24HR [product label]. US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/020468Orig1s035lbl.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- Flonase Sensimist Allergy Relief [product label]. US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/022051Orig1s014lbl.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- ClariSpray Nasal Allergy Spray [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2016.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescription to over-the-counter (OTC) switch list. https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ucm106378.htm. Updated February 27, 2017. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- Emanuel IA, Blaiss MS, Meltzer EO, Evans P, Connor A. Nasal deposition of ciclesonide nasal aerosol and mometasone aqueous nasal spray in allergic rhinitis patients. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28(2):117-121.

- Braido F, Lagasio C, Piroddi IMG, Baiardini I, Canonica GW. New treatment options in allergic rhinitis: patient considerations and the role of ciclesonide. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(2):353-361.

- Van Hoecke H, Vandenbulcke L, Van Cauwenberge P. Histamine and leukotriene receptor antagonism in the treatment of allergic rhinitis: an update. Drugs. 2007;67(18):2717-2726.

- Blaiss MS. Allergic rhinitis: direct and indirect costs. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(5):375-380.

- Fromer LM, Ortiz G, Ryan SF, Stoloff SW. Insights on allergic rhinitis from the patient perspective. J Fam Pract. 2012;61(2 suppl):S16-S22.

- Loh CY, Chao SS, Chan YH, Wang DY. A clinical survey on compliance in the treatment of rhinitis using nasal steroids. Allergy. 2004;59(11):1168-1172.

- Hellings PW, Dobbels F, Denhaerynck K, Piessens M, Ceuppens JL, De Geest S. Explorative study on patient’s perceived knowledge level, expectations, preferences and fear of side effects for treatment for allergic rhinitis. Clin Transl Allergy. 2012;2(1):9.

- Greiner AN, Hellings PW, Rotiroti G, Scadding GK. Allergic rhinitis. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2112-2122.

- Marple BF, Fornadley JA, Patel AA, et al; American Academy of Otolaryngic Allergy Working Group on Allergic Rhinitis. Keys to successful management of patients with allergic rhinitis: focus on patient confidence, compliance, and satisfaction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(6 suppl):S107-S124.

- Allen DB. Do intranasal corticosteroids affect childhood growth? Allergy. 2000;55(suppl 62):15-18.

- Sheth K. Evaluating the safety of intranasal steroids in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4(3):125-129.

- Skoner DP. The tall and the short: repainting the landscape about the growth effects of inhaled and intranasal corticosteroids. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37(3):180-191.

- Lee LA, Sterling R, Máspero J, Clements D, Ellsworth A, Pedersen S. Growth velocity reduced with once-daily fluticasone furoate nasal spray in prepubescent children with perennial allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):421-427.

- Skoner DP, Berger WE, Gawchik SM, Akbary A, Qiu C. Intranasal triamcinolone and growth velocity. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e348-e356.

- Blaiss MS. Safety considerations of intranasal corticosteroids for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28(2):145-152.

- Allen DB. Systemic effects of intranasal steroids: an endocrinologist’s perspective. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(4 suppl):S179-S190.

- Emin O, Fatih M, Emre D, Nedim S. Lack of bone metabolism side effects after 3 years of nasal topical steroids in children with allergic rhinitis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2011;29(5):582-587.

- Sastre J, Mosges R. Local and systemic safety of intranasal corticosteroids. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22(1):1-12.

- Omnaris [product monograph]. Oakville, ON, Canada: Takeda Canada Inc; 2015. http://www.takedacanada.com/omnarispm/~/media/countries/ca/files/product%20pdfs/omnarispm_eng_2015aug04.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- Mehuys E, Gevaert P, Brusselle G, et al. Self-medication in persistent rhinitis: overuse of decongestants in half of the patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(3):313-319.

- Mahadevia P, Shah S, Mannix S, et al. Willingness to pay for sensory attributes of intranasal corticosteroids among patients with allergic rhinitis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12(2):143-151.

- Mahadevia PJ, Shah S, Leibman C, Kleinman L, O’Dowd L. Patient preferences for sensory attributes of intranasal corticosteroids and willingness to adhere to prescribed therapy for allergic rhinitis: a conjoint analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93(4):345-350.

- Sher ER, Ross JA. Intranasal corticosteroids: the role of patient preference and satisfaction. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35(1):24-33.

- Blaiss MS, Meltzer EO, Derebery MJ, Boyle JM. Patient and healthcare-provider perspectives on the burden of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28(suppl 1):S4-S10.