Peer Reviewed

A Collection of Gastrointestinal Disorders

Gastrocolic Fistula After Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy

Authors:

Peter Le, MD

Annie Penn Hospital, Reidsville, North Carolina

Eduard Misse, MD, and Dwan Varner, MD

Vidant Roanoke-Chowan Hospital, Ahoskie, North Carolina

Citation:

Le P, Misse E, Varner D. Gastrocolic fistula after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Consultant. 2017;57(6):367-368.

A 64-year-old man was admitted to a hospital for aspiration pneumonia. He had had a prior cardiovascular accident (CVA) with dense right hemiplegia, aphasia, and dysphagia requiring tube feeding.

History. The patient’s percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube had been placed the previous month at another hospital. Two days after PEG tube placement, the patient developed a fever (temperature, 38.9°C). Blood culture test and urinalysis results at that time were negative for infection, a chest radiograph was clear, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings were unremarkable. The source of his fever remained unknown; accordingly, no antibiotics were started. He subsequently was discharged after spontaneous defervescence.

Physical examination. On this admission, his systolic blood pressure was 80 mm Hg, heart rate was 95 beats/min, temperature was 37.4°C, and respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min. He was alert but aphasic. Cardiac examination findings showed no murmur. Examination of the lungs revealed scattered rhonchi but no wheezing. Abdominal examination showed no distention, with the PEG tube on the left upper quadrant. He had no leg edema and had left hemiplegia.

Diagnostic tests. Initial laboratory test results showed no leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 4200/µL, a hemoglobin level of 11 g/dL, a urea nitrogen level of 39 mg/dL, a creatinine level of 0.8 mg/dL, and a lactate level of 2.7 mg/dL. Results of liver function tests showed elevated values, with an aspartate aminotransferase level of 136 U/L and an alanine aminotransferase level of 126 U/L. Chest radiography showed a right lower-lobe infiltrate.

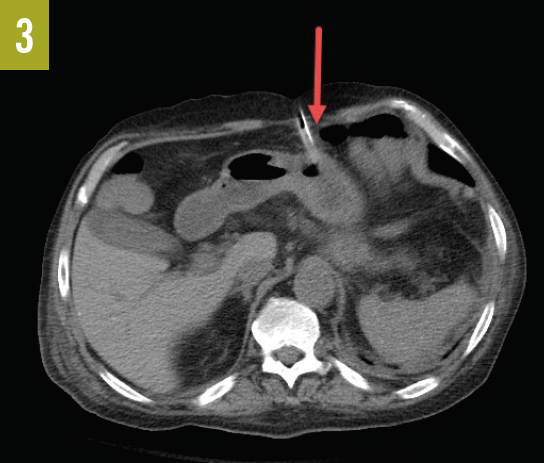

He was admitted for presumed aspiration pneumonia and was started on intravenous vancomycin and intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam. On hospital day 4, he experienced stool leakage around the PEG tube. His feeding tube was promptly discontinued, and CT with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis was performed. The CT showed correct placement of the PEG tube into the stomach, and no focal abscess was seen. A consultant surgeon had high clinical suspicion that during its placement, the PEG tube had pierced the transverse colon. A review of the patient’s prior medical records confirmed that he had spiked fevers 2 days after his PEG tube procedure.

A limited barium enema was performed. When the half-strength water-soluble contrast agent, introduced via a rectal catheter, entered the transverse colon, filling of the stomach also was observed (Figures 1-3). The site of continuity between the transverse colon and the stomach could not be determined. The diagnosis was made of gastrocolic fistula resulting from the PEG tube having traversed the transverse colon during placement.

Figure 1. Limited barium enema, prior to the contrast agent entering the stomach.

Figure 2. Barium contrast from the transverse colon can be seen spilling into the stomach, indicative of a gastrocolic fistula.

Figure 3. CT scan showing the proximity of the PEG tube and the transverse colon.

Outcome of the case. The patient was transferred to a tertiary medical center for laparoscopic corrective surgery.

Discussion. The patient population requiring PEG tube placement is generally debilitated, most often as a result of a CVA or other catastrophic event, and is more likely to have a do-not-resuscitate order and to not want invasive investigations to be performed if their condition deteriorates. Given this fact, it is likely that more cases such as our patient’s go undiagnosed and unrecognized. The incidence of this type of complication of PEG tube placement is unknown.

Continuous back-aspiration during PEG tube placement using a large syringe may help avoid this complication—should the PEG tube enter the transverse colon, a gush of air may be felt or heard.

Having a high clinical suspicion for gastrocolic fistula, along with persistent pursuit of investigation, are required to make such a diagnosis.

NEXT: Esophageal Varices in a Patient With Fatty Liver Disease

Esophageal Varices in a Patient With Fatty Liver Disease

Authors:

Vinh-Quang Do Nguyen, DO

Corpus Christi Medical Center – Bay Area, Corpus Christi, Texas

Raghujit Singh, MD

Abdominal Specialists of South Texas, Corpus Christi, Texas

Citation:

Nguyen VQD, Singh R. Esophageal varices in a patient with fatty liver disease. Consultant. 2017;57(6):368-370.

A 52-year-old man with a history of fatty liver disease presented with a 1-day history of abdominal pain and hematemesis. He reported 500 mL of coffee-ground vomitus. The patient denied having chest pain, dyspnea, hematochezia, and melena. He denied a history of alcohol use, gastrointestinal (GI) tract bleed, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and aspirin use. He had never received a diagnosis of esophageal varices or liver cirrhosis.

Physical examination. On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were stable. He did not have scleral icterus, gynecomastia, spider angioma, abdominal fluid wave, asterixis, peripheral edema, petechiae, or jaundice.

Diagnostic tests. Laboratory test results were significant for a white blood cell count of 17,700/µL (reference range, 4300-10,800/µL), a hemoglobin level of 8.7 g/dL (reference range, 14-18 g/dL); a hematocrit of 25.9% (reference range, 42%-52%); an alkaline phosphatase level of 170 U/L (reference range, 50-136 U/L); and a γ-glutamyltransferase level of 204 U/L (reference range, 5-55 U/L).

Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated an upper-normal size liver with fatty infiltration. Abdominal ultrasonography with color Doppler demonstrated no evidence of inferior vena cava, splenic, or portal vein thrombosis. Results of an acute hepatitis panel were negative. Antimitochondrial antibody test results were normal.

The patient was started on pantoprazole and octreotide drips upon admission. He received aggressive fluid resuscitation and blood transfusions as needed. He then underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which revealed that the hematemesis was secondary to large esophageal varices (Figure); accordingly, variceal band ligation (VBL) was performed.

Discussion. Esophageal varices are dilated submucosal veins in the esophagus. They are most often a consequence of portal hypertension, which is commonly a result of cirrhosis. Varices are present in approximately 50% of patients with cirrhosis.1 The prevalence of esophageal varices is 34.7% in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.2 The etiology of portal hypertension can be presinusoidal (portal vein thrombosis), sinusoidal (cirrhosis), and postsinusoidal (Budd-Chiari syndrome).

Patients with varices are at high risk for variceal bleeding. Without treatment, 25% to 40% of patients with varices will experience an episode of bleeding. Variceal bleeding is associated with a mortality of at least 20% at 6 weeks.1 Signs of bleeding from esophageal varices include vomiting blood, dark-colored or black tarry stools, bloody bowel movements, and syncope.

Varices are diagnosed with EGD. Patients with cirrhosis are advised to undergo elective endoscopic screening for varices at the time of diagnosis and periodically thereafter.3 Capsule endoscopy is another procedure used for screening for varices.

Interventions to prevent bleeding from esophageal varices include alcohol avoidance, weight loss, β-blocker therapy, and VBL. Alcohol can worsen cirrhosis and increase the risk of bleeding; thus, patients with cirrhosis are advised to avoid its consumption. Many patients with cirrhosis have fatty liver disease secondary to obesity, and weight loss can remove fat from the liver and may reduce further injury. Nonselective β-blockers such as propranolol and nadolol reduce portal pressures by decreasing cardiac output and by producing splanchnic vasoconstriction. Studies have shown that nonselective β-blockers decrease the risk for first variceal bleeding by 40% to 50% compared with placebo.4 VBL is used to treat and prevent acute variceal bleeding.

Patients with suspected acute variceal bleeding should be admitted directly to an intensive care unit for close monitoring and aggressive management. Initial resuscitation measures include large-bore intravenous access, blood work, and typing and cross-matching for blood products. Volume resuscitation should be promptly initiated but used with caution, because aggressive resuscitation can increase portal pressures and lead to rebleeding. Hemodynamic stability should be maintained with normal saline and blood products. There should be a low threshold to intubate the patient for airway protection, because aspiration of blood is common in cases of variceal bleeding.5

Antibiotics are recommended for all cirrhotic patients with upper GI tract bleeding.6 Octreotide, a somatostatin analogue, is commonly used to decrease portal venous pressure and increase clotting and hemostasis.7 Proton-pump inhibitor therapy is administered to maintain intragastric pH at 6 or greater to facilitate adequate clotting.8 EGD should be performed emergently to confirm the diagnosis and to allow the implementation of endoscopic therapy.

Despite the use of endoscopic and pharmacologic therapies, variceal bleeding cannot be controlled or recurs in up to 20% of patients.9 Portal compressive therapy, either shunt surgery or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), are considered in such cases.

Outcome of the case. The patient was started on a regimen of oral propranolol and pantoprazole. He was discharged in stable condition, with a plan for follow-up with his primary care physician and to undergo an extensive workup for the esophageal varices.

REFERENCES:

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace N, Carey WD; Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922-938.

- Nakamura S, Konishi H, Kishino M, et al. Prevalence of esophagogastric varices in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2008;38(6):572-579.

- de Franchis R; Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63(3):743-752.

- Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, et al; Portal Hypertension Collaborative Group. Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(21):2254-2261.

- Freeman ML. The current endoscopic diagnosis and intensive care unit management of severe ulcer and other nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 1991;1:209-239.

- Moon AM, Dominitz JA, Ioannou GN, Lowy E, Beste LA. Use of antibiotics among patients with cirrhosis and upper gastrointestinal bleeding is associated with reduced mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(11):1629-1637.e1.

- Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A. Somatostatin analogues for acute bleeding oesophageal varices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD000193.

- Netzer P, Gaia C, Sandoz M, et.al. Effect of repeated injection and continuous infusion of omeprazole and ranitidine on intragastric pH over 72 hours. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(2):351-357.

- García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al; Early TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) Cooperative Study Group. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2370-2379.

NEXT: Nasal Granulomatosis as an Extraintestinal Manifestation of Crohn Disease

Nasal Granulomatosis as an Extraintestinal Manifestation of Crohn Disease

Authors:

Joseph Spataro, MD; C. Andrew Kistler, MD, PharmD; Upasana Joneja, MD; and David Kastenberg, MD

Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Citation:

Spataro J, Kistler A, Joneja U, Kastenberg D. Nasal granulomatosis as an extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease. Consultant. 2017;57(6):370-372.

A 51-year-old woman with colonic Crohn disease (CD) presented with an exacerbation of chronic nasal congestion, as well as dysosmia, unilateral headaches, and facial pain of 4 weeks’ duration. She had experienced similar symptoms intermittently for the past 10 years without significant impact on activities of daily living. She had made several visits to otorhinolaryngology specialists, whose prescribed treatment regimens—including amoxicillin clavulanate, methylprednisolone dose packs, saline nasal sprays, and nasal corticosteroid nebulizers—had resulted in limited relief of the patient’s nasal congestion symptoms.

History. The patient denied cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, nasal trauma, a history of recent surgery, illicit drug use, or travel outside the Mid-Atlantic states. She reported no history of recent illnesses, tobacco use, allergies, periodontal disease, occupational or hobby-related exposures, or exposure to mold or pets.

The woman’s CD had been previously treated with 6-mercaptopurine and mesalamine, which had abated the gastrointestinal (GI) tract symptoms, and her condition had remained in remission for the past 2 years without additional treatment. Results of magnetic resonance enterography and colonoscopy of the terminal ileum were reported as normal 1 year prior to this presentation.

Physical examination. Physical examination findings included no parotid enlargement, oral ulceration, retinal vessel inflammation, digital ulcers, telangiectasias, or palpable adenopathy. Cardiopulmonary examination findings were normal. Muscle tone and range of motion were normal, and no joint warmth, pain with palpation of the joint lines, or effusions were present.

Diagnostic tests. Nasal endoscopy revealed bilateral limited airspace, nasal septal deviation, and bilateral crusting with diffusely friable, edematous mucosa.

Nasal septal mucosa biopsy results demonstrated acute and chronic inflammation with diffuse nonnecrotizing granulomas and 1 necrotizing granuloma (Figure 1). No fungi, acid-fast bacilli, or other bacterial organisms were identified on stain or culture tests, and no vasculitis was evident.

Figure 1. Histopathologic examination results of nasal biopsy specimens showing the respiratory mucosa with acute and chronic inflammation and a nonnecrotizing granuloma (arrow).

In consultation with specialists in otorhinolaryngology and rheumatology, the list of differential diagnoses for sinonasal granulomatosis included collagen vascular disease, vasculitis, and infection.

Results of laboratory studies, including tests for antinuclear antibodies, anti-ribonucleoprotein antibodies, anti-Sjögren syndrome type A and B antibodies, antineutrophil and cytoplasmic antibodies, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and atypical antibodies, were negative. Infectious serology test results, including QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube tuberculosis antigen testing and rapid plasma reagin testing, were nonreactive. Findings of computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest were normal, and CT scans of the sinuses demonstrated septal deviation with minimal sinus mucosal thickening.

Results of an extensive evaluation for collagen vascular disease, infection, and other processes associated with sinonasal granulomatous lesions were negative. Based on the otorhinolaryngologist’s recommendation, the patient was started on a 2-week course of amoxicillin clavulanate, saline nasal sprays, and nasally administered decongestants with steroids, including fluticasone and budesonide, for a differential diagnosis of sinusitis vs vasculitis. Repair of the septal deviation was not offered given the strong suspicion that one of the aforementioned diagnoses was causing the patient’s symptoms.

After 6 weeks of treatment without symptomatic relief, the patient reported new-onset abdominal pain and diarrhea, along with a 4.5-kg weight loss. Results of an infectious GI pathogen panel were negative, including for Clostridium difficile. Colonoscopy findings (Figure 2) showed mild discontinuous mucosal ulceration without bleeding throughout the large intestine, and biopsy results (Figure 3) confirmed chronic active colitis with mucosal epithelioid granulomas.

Figure 2. Endoscopic view of the cecum and ascending colon with evidence of ulceration.

Figure 3. Histopathologic examination results of biopsy specimens from the cecum showing intraepithelial mixed inflammation and a nonnecrotizing epithelioid granuloma (arrow) in the colonic mucosa.

In response to a relapse of CD, she was treated with prednisone, 60 mg daily, with a gradual taper over 5 weeks. Although her GI tract symptoms improved, there was only a transient improvement in her ear, nose, and throat symptoms, which recurred with tapering of steroids. At that time, nasal endoscopy results confirmed active sinus disease. Given her recurrent symptoms upon steroid taper, her limited symptom relief with nasal steroids, her active colonic disease, and the morbidity associated with long-term high-dose steroid use, an antitumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) agent was recommended. However, because of the patient’s concern about the potential adverse effects associated with anti-TNF-α agents, maintenance therapy with mesalamine (2.4 g/d orally), methotrexate (15 mg/wk subcutaneously), and prednisone (40 mg/d orally) was initiated.

Outcome of the case. After 6 weeks, the patient reported mild improvement in her nasal symptoms and resolution of the abdominal pain with regular bowel movements. The patient agreed to a steroid taper with consideration of an anti-TNF-α agent should her symptoms recur.

Discussion. CD is a subtype of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that is characterized by transmural, discontinuous inflammation of the GI tract, usually associated with granulomas.1,2 Sinonasal disease is a rare extraintestinal manifestation (EIM) of CD and can be a diagnostic challenge.

In 1985, Kinnear and colleagues3 first described nasal CD and considered it a manifestation of relapsed disease. The severity of sinonasal inflammation and associated symptoms may parallel or occur independent of CD activity in the GI tract.2,4,5 Sinonasal symptoms associated with CD include nasal congestion, dysosmia, rhinorrhea, epistaxis, and structural deformities.2,6 Nasal endoscopic findings include mucosal inflammation, ulceration, atrophic rhinitis with nasal crusting, necrosis of the turbinates, and, rarely, septal perforation.2

The pathogenesis is speculative but may be related to GI mucosal inflammation causing increased bowel permeability. Subsequently, luminal antigen exposure may activate an immune response with release of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins 1 and 12 and TNF-α.4 In a review of 700 patients with IBD in the 1970s, Greenstein and colleagues7 found that patients with granulomatous colitis CD had an increased risk for EIMs compared with patients with isolated small bowel disease. In a more recent retrospective study of 811 patients with IBD in Italy, including 216 with CD, Zippi and colleagues8 reported EIMs in 55.1% of patients with CD, with the most common EIMs being musculoskeletal (peripheral arthritis), mucocutaneous (erythema nodosum, aphthous stomatitis), and ocular (episcleritis, uveitis).

Of the 9 cases of nasal CD documented in the literature,1-3,5,6,9-11 approximately half describe granulomatous inflammation. The presence of granulomas on histopathologic examination is consistent but not pathognomonic for CD, and other granulomatous processes must be excluded, the differential diagnosis of which is extensive (Table).2,12

Nasal CD may be responsive to topical steroids; however, if topical steroids are ineffective or if nasal manifestations of CD occur concomitantly with intestinal manifestations, systemic therapy with glucocorticosteroids and/or anti-TNF-α agents should be considered.1,4 Isolated nasal CD may respond to nasal steroids, including beclomethasone.1 Nasal CD with concomitant intestinal disease may respond to a combination of topical and systemic corticosteroids for several weeks followed by a taper, and the addition of a steroid-sparing agent such as 6-mercaptopurine or azathioprine.2,5,6,9 An anti-TNF-α agent is recommended with steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent CD.4,13

In patients with CD with severe or refractory sinonasal symptoms, extraintestinal CD should be considered. Confirmation of sinonasal CD requires a biopsy, but the presence of granulomas is not specific for CD; thus, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and particular care should be taken to ensure that the finding is not infectious or autoimmune in etiology.

In our patient’s case, the histologic findings on nasal biopsy, the exclusion of infectious or inflammatory causes of granulomatous disease, and the rapid response to systemic glucocorticosteroids suggested that her symptoms were a sinonasal EIM of CD.

REFERENCES:

- Pellicano R, Sostegni R, Sguazzini C, Reggiani S, Astegiano M. A rare location of Crohn’s disease: the nasal mucosa. Acta Biomed. 2011;82(1):74-76.

- Eloy P, Leruth E, Goffart Y, et al. Sinonasal involvement as a rare extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn’s disease. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(1):103-108.

- Kinnear WJ. Crohn’s disease affecting the nasal mucosa. J Otolaryngol. 1985;14(6):399-400.

- Zois CD, Katsanos KH, Tsianos EV. Ear-nose-throat manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. Ann Gastroenterol. 2007;20(4):265-274.

- Ulnick KM, Perkins J. Extraintestinal Crohn’s disease: case report and review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80(2):97-100.

- Baili L, Rachdi I, Daoud F, et al. A rare manifestation of Crohn’s disease: sinonasal granulomatosis. Report of a case and review of literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2014;1. doi:10.12890/2014_000123

- Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD, Sachar DB. The extra-intestinal complications of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a study of 700 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55(5):401-412.

- Zippi M, Corrado C, Pica R, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations in a large series of Italian inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(46):17463-17467.

- Wiesen A, Oustecky D, Bandovic J, Blanche FL, Perlman P, Katz S. Leukocytapheresis in the treatment of nasal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2008;4(2):125-127.

- Pochon N, Dulguerov P, Widgren S. Nasal manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113(6):813-815.

- Ernst A, Preyer S, Plauth M, Jenss H. Polypoid pansinusitis in an unusual, extra-intestinal manifestation of Crohn disease [in German]. HNO. 1993;41(1):33-36.

- Montone KT. Differential diagnosis of necrotizing sinonasal lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(12):1508-1514.

- Schwartz DA. Nasal Crohn’s disease/apheresis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2008;4(2):127-128.