Peer Reviewed

A Collection of Conditions Affecting the Lungs

Large Pulmonary Embolus With Unilateral Hyperlucent Lung

Authors:

Min Qiao, MD; Vishaal Gupta; Olivia Onwodi; and Rajat Mukherji, MD

Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York

Citation:

Qiao M, Gupta V, Onwodi O, Mukherji R. Large pulmonary embolus with unilateral hyperlucent lung. Consultant. 2017;57(10):596-597.

A 91-year-old woman presented to the hospital with acute onset of dyspnea and pain and swelling of the left leg.

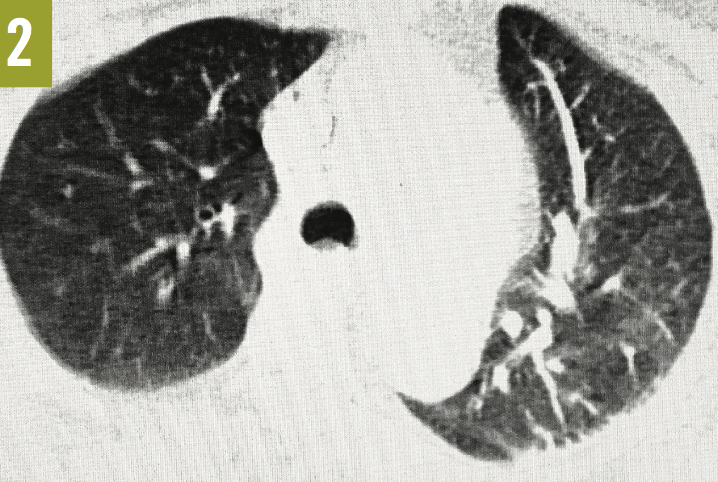

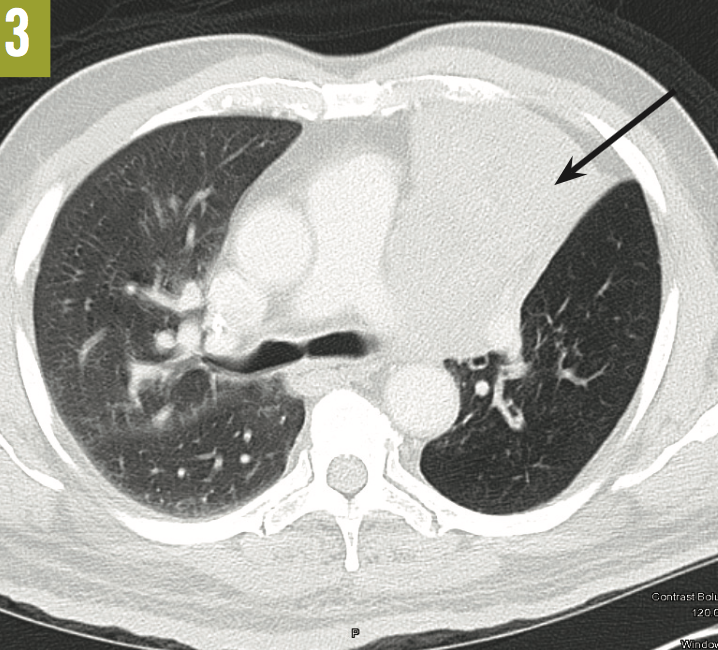

Venous duplex ultrasonography of the left leg confirmed the presence of deep-vein thrombosis. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the chest showed a large embolus in the right main pulmonary artery, almost completely occluding the lumen of the vessel (Figure 1). A few peripheral emboli were present in the left lung, as well. Perfusion to the entire right lung was markedly diminished, and there was a compensatory increase in the perfusion of the left lung (Figures 2 and 3). The radiographic findings were consistent with the Westermark sign.

Figure 1: Axial CTA of the chest showed a large embolus (arrowhead) in the right main pulmonary artery.

Figure 2: Axial CTA of the chest also showed severe hypovascularity of the right lung with a compensatory increase in the vascularity of the left lung (the Westermark sign).

Figure 3: Coronal CTA of the chest showed markedly reduced vascularity of the right lung and compensatory hypervascularity of the left lung.

The patient was hemodynamically stable and was treated successfully with enoxaparin and later switched to warfarin.

Discussion. The Westermark sign is a relatively rare radiographic finding that is seen in approximately 2% of patients with confirmed pulmonary embolism (PE).1 The responsible embolus usually lodges in a main or lobar branch of the pulmonary artery. Chest radiographs or chest CT scans show a paucity of vascular markings (oligemia) in the lung parenchyma distal to the embolic obstruction. The affected area looks darker (hyperlucent) compared with the rest of the lung.

The radiographic findings of localized or unilateral hyperlucency may mimic localized bullous disease or unilateral emphysema (Swyer-James syndrome [SJS]). The latter is characterized by unilateral hyperlucency caused by postinfectious hypoplasia of the vasculature and parenchyma of 1 lung.2 The process begins in childhood as bronchiolitis obliterans and manifests later as emphysematous change in the affected lung.

An acute exacerbation of SJS may mimic acute PE, with clinical manifestations such as acute-onset dyspnea with hypoxemia. In such patients, when chest radiographs reveal unilateral hyperlucency, an incorrect diagnosis of acute PE with the Westermark sign may be made.3 CTA of the chest would establish the correct diagnosis.

Apart from SJS, acquired unilateral emphysema may be the result of previous necrotizing pneumonia, wherein the lung parenchyma is disrupted by the infectious process.4

Unilateral hyperlucent lung is also seen in rare instances of an endobronchial lesion, such as a foreign body or tumor.5 In this circumstance, the lesion in the bronchus works in a check-valve mechanism, allowing air to enter during inspiration but retarding adequate deflation during expiration. The clue to this diagnosis is on chest radiographs. When the radiograph is taken during inspiration, both lungs are equally expanded. During expiration, the affected lung with the endobronchial lesion remains inflated and looks relatively hyperlucent compared with the opposite lung, which deflates and looks smaller.

In our patient, the embolus almost completely obstructed the right main pulmonary artery, causing much of the output from the right ventricle to be diverted from the right lung into the left lung. This resulted in a relatively dark lung field on the right and a highly congested lung on the left. Oligemia in the embolized lung is largely due to anatomic obstruction of blood flow by the embolus. However, another contributory factor is the physiologic effect of hypoxic vasoconstriction, which further reduces perfusion to the embolized lung.6

REFERENCES:

- Worsley DF, Alavi A, Aronchick JM, Chen JT, Greenspan RH, Ravin CE. Chest radiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: observations from the PIOPED Study. Radiology. 1993;189(1):133-136.

- Mori J, Kaneda D, Fujiki A, Isoda K, Kotani T, Ushijima Y. Swyer-James syndrome in a 7-year-old female. Pediatr Rep. 2016;8(3):6643.

- Akgedik R, Karamanli H, Aytekin İ, Kurt AB, Öztürk H, Dağlı CE. Swyer-James-Macleod syndrome mimicking an acute pulmonary embolism: a report of six adult cases and a retrospective analysis [published online July 12, 2016]. Clin Respir J. doi:10.1111/crj.12529

- Chatha N, Fortin D, Bosma KJ. Management of necrotizing pneumonia and pulmonary gangrene: a case series and review of the literature. Can Respir J. 2014;21(4):239-245.

- Vimala LR, Sathya RKBS, Lionel AP, Kishore JS, Navamani K. Unilateral obstructive emphysema in infancy due to mediastinal bronchogenic cyst—diagnostic challenge and management. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(5):TD03-TD05.

- Burrowes KS, Clark AR, Wilsher ML, Milne DG, Tawhai MH. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction as a contributor to response in acute pulmonary embolism. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42(8):1631-1643.

NEXT: Atelectasis

Atelectasis

Authors:

Vishal Patel, MD; Rahul Gupta, MS-III; Rachna Kumar, MS-III; Rajat Mukherji, MD; Viplov Mehta, MD; and Harish Patel, MD

Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York

Citation:

Patel V, Gupta R, Kumar R, Mukherji R, Mehta V, Patel H. Atelectasis. Consultant. 2017:57(10):597-598.

A 77-year-old man with a 45 pack-year history of smoking was admitted for cough, dyspnea upon mild exertion, and weight loss. The cough was productive of whitish sputum without hemoptysis. The patient denied chest pain, night sweats, and fever.

A posteroanterior chest radiograph showed an opacity suggestive of an infiltrate along the left paracardiac area (Figure 1). On lateral view, the left cardiac margin was not distinctly visualized and appeared to merge with the infiltrate, suggesting that the infiltrate was anteriorly situated; a broad linear density was noted in the retrosternal area, extending from the apex of the lung to the base (Figure 2). Community-acquired pneumonia was the admitting diagnosis; however, computed tomography scanning of the chest revealed total atelectasis of the left upper lobe (Figure 3).

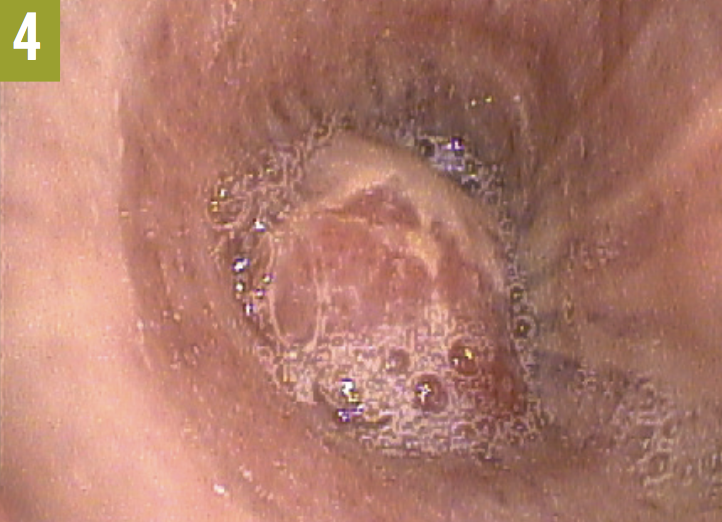

Bronchoscopy was performed, the results of which showed the presence of an endobronchial lesion completely occluding the left main bronchus (Figure 4). Biopsy revealed the lesion to be a well-differentiated de novo squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 5).

Discussion. Left upper lobe atelectasis can mimic a pneumonic process on chest radiographs. The findings frequently are of a density that looks like an infiltrate in the left paracardiac area, possibly leading to a misdiagnosis of pneumonia. Clues to making the correct radiographic diagnosis of left upper lobe atelectasis include the uniformity of the density, its proximity to the left side of the heart, and the fact that the density merges with the cardiac shadow. On lateral films, a wide, opaque band situated in front of the heart is noted.

The lingular segment of the left upper lobe lies adjacent to the left side of the heart, which itself is an anteriorly situated organ. The left upper lobe, when airless, collapses and contracts medially and anteriorly, positioning itself adjacent to the heart. Radiopaque structures lying adjacent to each other lose their distinguishing borders and tend to merge on the radiograph (the silhouette sign).1,2 This was the situation in our patient’s case—the image of the collapsed left upper lobe merged with the cardiac shadow, giving the appearance of the presence of a paracardiac infiltrate.

This patient’s case illustrates the fact that an apparent infiltrate in the left paracardiac area, wherein the left heart margin is lost, may have more than one differential diagnosis. Pneumonia in this situation usually involves the lingular section of the left upper lobe. Another possibility, as this patient’s case demonstrates, is either partial or complete atelectasis involving the left upper lobe. Establishing the correct diagnosis early is essential to managing such cases and achieving the best outcome for the patient.

REFERENCES:

- Bell DJ, Goel A. Silhouette sign (x-rays). Radiopaedia. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/silhouette-sign-x-rays. Accessed September 25, 2017.

- Terquem EL, L’Her P. The silhouette sign (Felson) and its derivatives. International Society of Radiology. http://www.isradiology.org/2017/goed_tb_project/slide_spi/3%20Silhouet%20sign.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2017.

NEXT: Streptococcus pneumoniae Phlegmon

Streptococcus pneumoniae Phlegmon

Authors:

Jennifer Kinaga, MD, and Michael Cancio, MD

Orlando Regional Medical Center, Orlando, Florida

Citation:

Kinaga J, Cancio M. Streptococcus pneumoniae phlegmon. Consultant. 2017;57(10):599-600.

A 65-year-old man presented with chest pain that radiated to his left shoulder and arm. The chest pain was midsternal, worsened with deep inspiration and minimal palpation, and was associated with dyspnea and nausea.

The patient had recently visited an orthopedist, who had administered a corticosteroid injection to the man’s back as treatment for upper back pain. He also had undergone a workup for chest pain the prior year, with normal nuclear stress test results. His medical history included hypertension, nonobstructive coronary artery disease, insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, and dextrocardia. He had a 40 pack-year history of smoking but denied any illicit drug use or alcohol use in the past year.

Physical examination. At presentation, the patient was afebrile. His heart rate was 120 beats/min and his blood pressure was 153/89 mm Hg; the rest of his vital signs were unremarkable. On examination, he had reproducible left-sided chest tenderness with increased warmth but no erythema. The left arm also was tender to palpation and movement, and the left shoulder was noted to have mild swelling. Cardiovascular examination revealed sinus tachycardia, with no murmurs, and 4+ pulses bilaterally. His lungs were clear to auscultation.

Diagnostic tests. Results of troponin and procalcitonin tests were normal. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus tachycardia with no acute ischemic changes. Chest radiography findings were negative for acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities (Figure 1). Due to an elevated D-dimer level, a computed tomography angiography (CTA) scan of the thorax was obtained, the results of which showed no pulmonary embolism or infiltrate. The patient was admitted to rule out acute coronary syndrome and underwent transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), the results of which showed an ejection fraction of 55% to 59% with no valvular vegetations. He was discharged home.

Figure 1: A chest radiograph showed dextrocardia and no acute abnormalities.

On hospital day 2, the patient became febrile (temperature, 38.6°C), with continuing chest, back, and shoulder pain. The results of multiple sets of blood cultures were negative for infection. His C-reactive protein level was elevated at 14 mg/L, and his erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 75 mm/h. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning of the cervical and thoracic spine showed right mastoiditis but no osteomyelitis or diskitis.

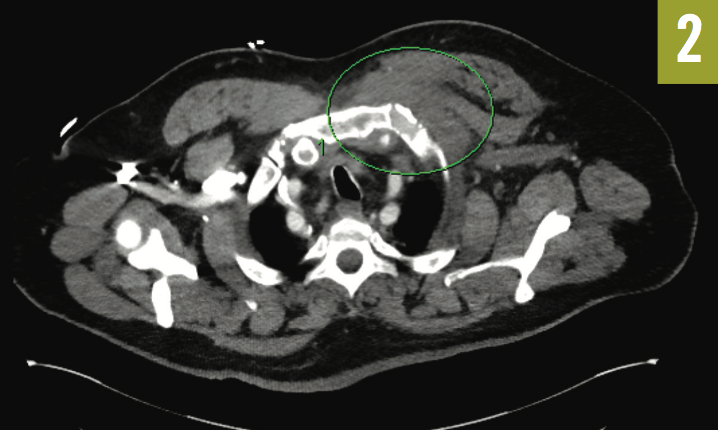

Given the clinical picture and concern for sternoclavicular septic arthritis, the thoracic CTA scan was reviewed with the radiologist, who noted an abnormal soft-tissue prominence (Figure 2). A CT-guided biopsy was performed inferior to the medial clavicle, and although no drainable abscess was found, purulent material was aspirated, culture results of which later returned positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Figure 2: Thoracic CTA showed dextrocardia and an abnormal soft-tissue prominence.

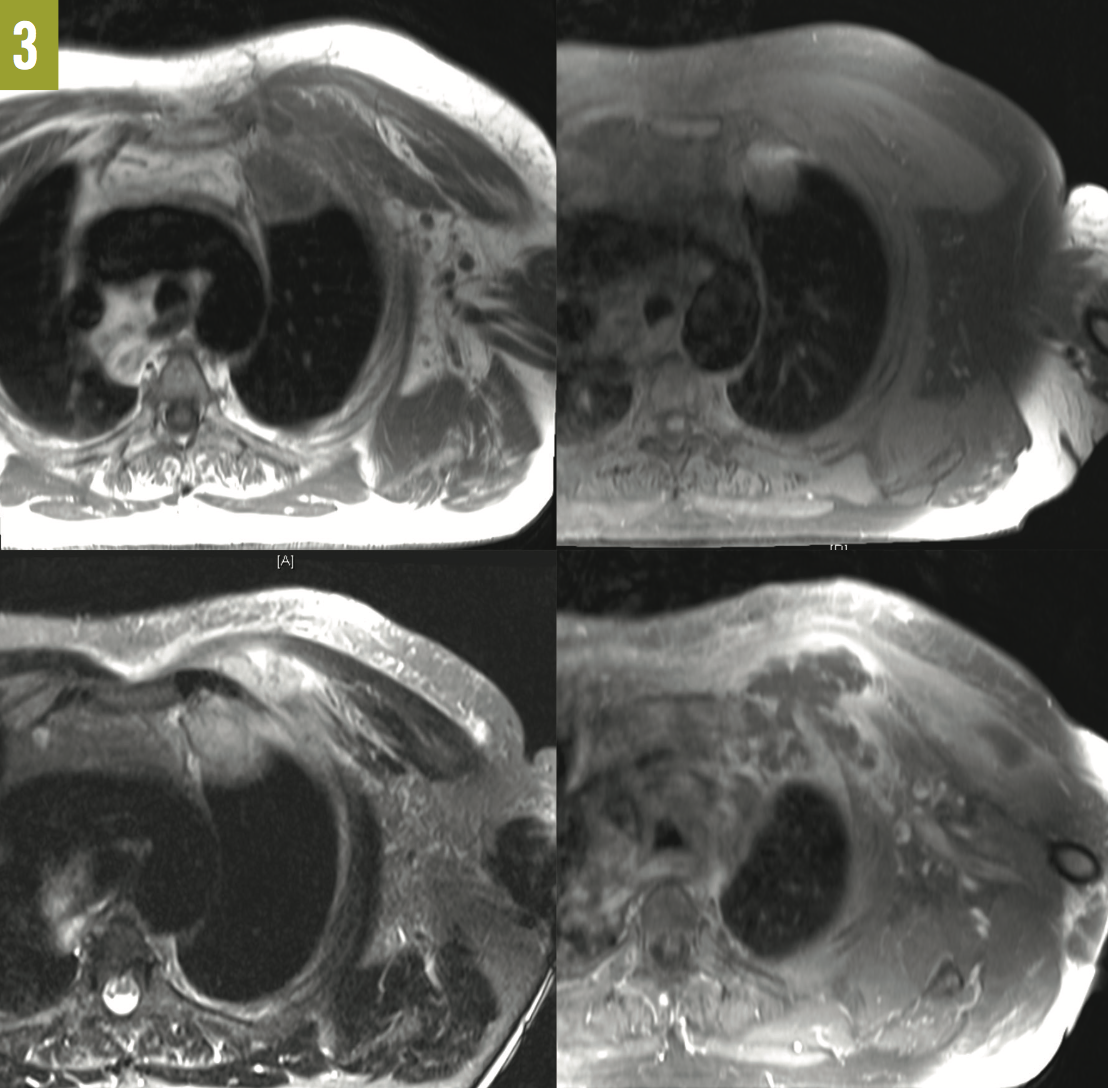

Outcome of the case. The patient was placed on broad-spectrum antibiotics, which later were narrowed to ceftriaxone. Due to continuing purulent discharge from the biopsy site, an MRI of the chest was ordered, the results of which showed a left anterior chest wall inflammatory phlegmon that extended from between the first and second ribs into the left apical subpleural space, along with marrow abnormalities of the mid left clavicle and lateral first rib suggestive of osteomyelitis (Figure 3).

Figure 3: MRI scans of the chest showed a left anterior chest wall phlegmon. Top left, T1-weighted turbo spin-echo (TSE) axial view; top right, T1-weighted TSE fat-saturated (FS) axial view; bottom left, T2-weighted short-tau inversion recovery axial view; and bottom right, T1-weighted TSE FS axial posterior view.

Discussion. Cellulitis and osteomyelitis are often caused by Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-hemolytic streptococci.1 S pneumoniae is a common cause of pneumonia in adults but rarely causes cellulitis, deep-tissue infections, and osteomyelitis.2,3 S pneumoniae cellulitis presents as 2 different syndromes. The first involves patients at risk for extremity injury and bacterial inoculation, such as those who have diabetes, use intravenous drugs, and abuse alcohol. Such patients usually present with cellulitis of the extremities from S pneumoniae. The second syndrome involves patients with autoimmune or hematologic disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus and usually presents with cellulitis of the head, neck, and upper torso.3

Our patient’s prior corticosteroid injection was a possible cause of his chest wall phlegmon, with the additional risk factor of diabetes. Although the occurrence rate of major adverse events from extra-articular corticosteroid injections is relatively low, cellulitis and localized abscess formation are possible, albeit rare.4

Another possible etiology of the patient’s phlegmon was his mastoiditis. Approximately 55% of S pneumoniae cellulitis cases involve an associated alternative source, usually the ears, the nasopharynx (where S pneumoniae is a common organism), the lower respiratory tract, or a joint.5 Our patient, however, was not bacteremic and thus was less likely to develop a chest phlegmon from hematogenous spread; moreover, the phlegmon was on the patient’s left side, while the mastoid disease was right-sided.

The patient underwent transesophageal echocardiography, the results of which—like the results of earlier TTE—showed no vegetations. In patients with pneumococcal cellulitis, 90% to 92% have been shown to have positive blood cultures,6 but culture results were negative in our patient’s case.

In 50% of patients with S pneumoniae cellulitis, surgical treatment is needed due to suppurative complications.5 Because of the location, depth, and possible clavicular and rib involvement of our patient’s phlegmon, a cardiothoracic surgeon was consulted. The patient underwent surgical anterior chest wall debridement of the soft tissues with wound vacuum placement, followed by another irrigation and drainage of the chest wound a few days later. Although there was a large amount of submuscular purulence, with an additional pocket communicating with the pleura, there was no empyema and no lung involvement. The sternoclavicular joint and the first and second ribs were strong and non-necrotic. The patient continued to improve and was discharged home on a regimen of intravenous ceftriaxone for a total of 6 weeks.

REFERENCES:

- Merlino JI, Malangoni MA. Complicated skin and soft-tissue infections: diagnostic approach and empiric treatment options. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(suppl 4):S21-S28.

- Capdevila O, Grau I, Vadillo M, Cisnal M, Pallares R. Bacteremic pneumococcal cellulitis compared with bacteremic cellulitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22(6):337-341.

- Parada JP, Maslow JN. Clinical syndromes associated with adult pneumococcal cellulitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32(2):133-136.

- Brinks A, Koes BW, Volkers ACW, Verhaar JAN, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Adverse effects of extra-articular corticosteroid injections: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:206.

- Bachmeyer C, Martres P, Blum L. Pneumococcal cellulitis in an immunocompetent adult. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(2):199-201.

- Lawlor MT, Crowe HM, Quintiliani R. Cellulitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(1):247-250.