Allergic Rhinitis: A Review of Treatment Options

Authors:

Ericka Howard, BA; Adriana Morell-Pacheco, BS; and Lynnette Mazur, MD, MPH

McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Citation:

Howard E, Morell-Pacheco A, Mazur L. Allergic rhinitis: a review of treatment options. Consultant. 2018;58(7):e193.

A 14-year-old girl presented with itchy and watery eyes, nasal congestion and pruritus, sneezing, and a scratchy throat—the classic symptoms of allergic rhinitis (AR). Her symptoms waxed and waned throughout the year but were worse in the spring and fall. She had no history of eczema or asthma and had no known drug or food allergies. Her parents smoked cigarettes in the home, and there were no pets. Physical examination findings were significant for allergic shiners, Dennie Morgan lines, 3 transverse nasal creases, and boggy nasal turbinates (Figure).

NEXT: AR Risk Factors

AR RISK FACTORS

AR is an immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated inflammatory response of the nasal mucosa induced by allergen exposure.1 There are 2 types of AR, seasonal and perennial. Seasonal AR occurs after exposure to aeroallergens such as weed and tree pollens, whose presence varies with geographic location and climate. Perennial AR results from exposure to year-round allergens such as molds and dust mites.2

Children with a history of atopic diseases such as rhinoconjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis, and food allergies are at increased risk of developing AR.3 The risk of developing otitis media with effusion is increased in patients with AR.4 Other risk factors for developing AR include white ethnicity, a family history of atopy, higher socioeconomic status, environmental pollution, and exposure to tobacco smoke.3,5 Additionally, AR is a significant risk factor and a trigger for asthma, and the severity of asthma is correlated with the severity of AR.1

Worldwide, AR affects approximately 400 million people and is increasing in prevalence.3 In the United States in 2012, 17.6 million (7.5%) adults and 6.6 million (9%) children received a diagnosis of AR or reported having AR in the past 12 months.6 In the United States in 2010, 11.1 million physician visits resulted in a diagnosis of AR.6

The increased prevalence of AR in urban areas may be related to the “Western lifestyle” and/or outdoor pollution and may be partly explained by the hygiene hypothesis.1 The hygiene hypothesis suggests that early-life exposures shape the immune system to either a type 1 helper T cell (TH1) nonallergic profile or a type 2 helper T cell (TH2) allergic profile, whereas a “sterile” environment is thought to shift the immune system into a TH2 profile and promote the development of allergic diseases.1

NEXT: Diagnosis & Treatment

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of AR in children and adults usually rests on history and physical examination findings. If the diagnosis is unclear or if therapy fails, referral to a subspecialist for allergen-specific testing may be helpful.7 Although IgE blood testing avoids the risk of anaphylaxis and difficulty with test interpretation compared with skin prick testing, the average sensitivity of IgE blood testing is lower, ranging from 70% to 75%.8 Nevertheless, the decision for testing is left to clinical discretion and the availability of a subspecialist.7

AR has a high comorbidity with asthma, depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, although a causal relationship has not been established.9 Although patients and clinicians may consider AR a nuisance and not pursue treatment, proper treatment can greatly improve quality of life.

TREATMENT

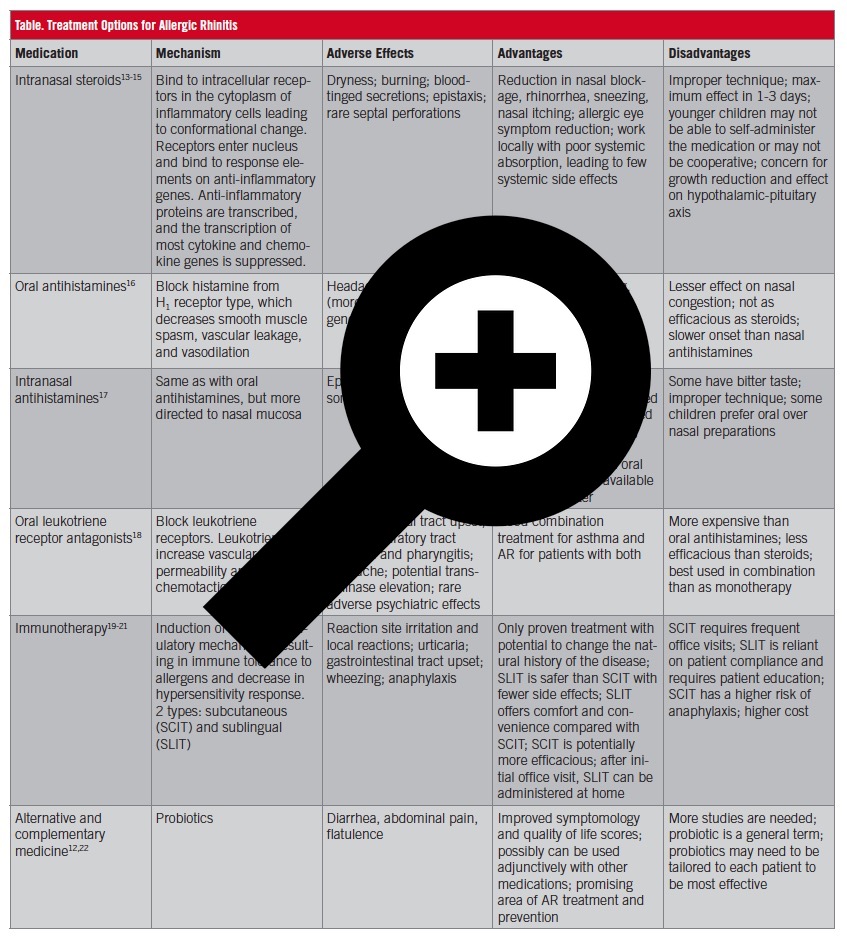

Treatment options include environmental, complementary, and pharmacologic strategies (Table). Environmental control measures and lifestyle modifications are encouraged for all patients with AR. The removal of pets from the home, the use of acaricides, and combined strategies such as washing pets twice a week, using air filters, and using impermeable bed covers effectively reduce symptoms in persons with pet and dust mite allergies.7,10

Table. Treatment Options for Allergic Rhinitis

Because of variations in patient symptomology and treatment preferences, guidelines provide clinical scenarios rather than algorithms to guide decision-making.7 For patients with mild or intermittent symptoms, oral antihistamines are recommended due to their low cost and fast onset of action. Intranasal antihistamines are recommended for patients with moderate to severe symptoms and for patients with intermittent symptoms.7 Intranasal steroids (INS) are recommended for patients with predominantly nasal congestion and those with moderate to severe symptoms.7 If monotherapy fails, combination therapy and immunotherapy are available.

Although complementary and alternative therapies have been used for the treatment of AR, their efficacy is not supported by the available scientific evidence, and accordingly no recommendation has been made in the guidelines.7 In the case of probiotics, the results of a recent meta-analysis showed that probiotics significantly reduced nasal and ocular symptoms scores.11

NEXT: The Take-Home Message

THE TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

AR is a disease that can vary in presentation, severity, and precipitants. Between office visits and prescription medications, approximately $3.4 billion is spent annually in the United States.12 Early effective treatment improves quality of life and can reduce the occurrence of sleep disorders, learning disabilities, and asthma exacerbations.

Due to the severity of our patient’s symptoms, she received a diagnosis of perennial allergies and was started on oral antihistamines and an INS.

Ericka Howard, BA, is a student at the McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Adriana Morell-Pacheco, BS, is a student at the McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Lynnette Mazur, MD, MPH, is a professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

REFERENCES:

- Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008. Allergy. 2008;63(suppl 86):8-160.

- Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2 suppl):S1-S84.

- Greiner AN, Hellings PW, Rotiroti G, Scadding GK. Allergic rhinitis. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2112-2122.

- Kreiner-Møller E, Chawes BLK, Caye-Thomasen P, Bønnelykke K, Bisgaard H. Allergic rhinitis is associated with otitis media with effusion: a birth cohort study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(11):1615-1620.

- Shargorodsky J, Garcia-Esquinas E, Navas-Acien A, Lin SY. Allergic sensitization, rhinitis, and tobacco smoke exposure in U.S. children and adolescents. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(6):471-476.

- Allergy statistics. American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology. http://www.aaaai.org/about-aaaai/newsroom/allergy-statistics. Accessed May 7, 2018.

- Seidman MD, Gurgel RK, Lin SY, et al. Clinical practice guideline: allergic rhinitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(1 suppl):S1-S43.

- Bernstein IL, Li JT, Bernstein DI, et al. Allergy diagnostic testing: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(3 suppl 3):S1-148.

- Schmitt J, Stadler E, Küster D, Wüstenberg EG. Medical care and treatment of allergic rhinitis: a population-based cohort study based on routine healthcare utilization data. Allergy. 2016;71(6):850-858.

- Hodson T, Custovic A, Simpson A, Chapman M, Woodcock A, Green R. Washing the dog reduces dog allergen levels, but the dog needs to be washed twice a week. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(4):581-585.

- Güvenç IA, Muluk NB, Mutlu FŞ, et al. Do probiotics have a role in the treatment of allergic rhinitis? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2016;30(5):157-175.

- Meltzer EO, Bukstein DA. The economic impact of allergic rhinitis and current guidelines for treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106(2 suppl):S12-S16.

- Hoover RM, Erramouspe J, Bell EA, Cleveland KW. Effect of inhaled corticosteroids on long-term growth in pediatric patients with asthma and allergic rhinitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(9):1175-1181.

- Al Sayyad JJ, Fedorowicz Z, Alhashimi D, Jamal A. Topical nasal steroids for intermittent and persistent allergic rhinitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD003163. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003163.pub4

- Hampel FC Jr, Nayak NA, Segall N, Small CJ, Li J, Tantry SK. No hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function effect with beclomethasone dipropionate nasal aerosol, based on 24-hour serum cortisol in pediatric allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(2):137-142.

- Simons FER, Simons KJ. Histamine and H1-antihistamines: celebrating a century of progress. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(6):1139-1150.

- Kaliner MA, Berger WE, Ratner PH, Siegel CJ. The efficacy of intranasal antihistamines in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106(2 suppl):S6-S11.

- Yilmaz O, Altintas D, Rondon C, Cingi C, Oghan F. Effectiveness of montelukast in pediatric patients with allergic rhinitis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77(12):1922-1924.

- Radulovic S, Wilson D, Calderon M, Durham S. Systematic reviews of sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). Allergy. 2011;66(6):740-752.

- Di Bona D, Plaia A, Scafidi V, Leto-Barone MS, La Piana S, Di Lorenzo G. Efficacy of subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy with grass allergens for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a meta-analysis–based comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(5):1097-1107.

- Durham SR, Penagos M. Sublingual or subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(2):339-349.e.10.

- Zajac AE, Adams AS, Turner JH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of probiotics for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(6):524-532.