What is the cause of hair loss in this 11-year-old?

HISTORY

An 11-year-old girl with a patch of hair loss that had suddenly appeared in the vertex of the scalp. There was no history of habitual hair pulling. The child’s past health was unremarkable. She was not taking any medication. The hair loss could not be attributed to any identifiable emotional stress. All family members were healthy, with no similar hair loss.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Vital signs normal. Ovoid patch of hair loss in the vertex of the scalp, with no scaling, scarring, or erythema. Remaining hairs normal. All other examination findings, in particular the fingernail and toenail findings, normal.

WHAT’S YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

(Answer on Next Page)

Answer: Alopecia areata

The hallmark of alopecia areata is the sudden loss of hair in a well-demarcated, localized area of the scalp.1 The hair loss is generally limited to a single patch, although it can be in the form of multiple patches.2 The lesion is usually round or oval. The scalp typically appears normal.1 “Exclamation point hairs” (short broken hairs that are broader at the distal end than at the scalp level) are frequently seen at the periphery of the lesion.1,3 Alopecia areata is often asymptomatic.

Nail involvement, particularly nail pitting, is found in 10% to 40% of affected children.1 Autoimmune diseases, notably thyroid autoimmunity, are the most significant association.2 Other associated autoimmune diseases include atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, pernicious anemia, diabetes mellitus, lupus erythematosus, Addison disease, autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1, and celiac disease.3 In children with Down syndrome, there is an increased incidence of alopecia aerata.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The lifetime risk of alopecia areata in the general population is about 1.7%.3 As many as 60% of patients with alopecia areata have disease onset before 20 years of age.2 The onset is rare before 2 years of age.1 The sex ratio is equal.3

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Alopecia areata is a tissue-specific autoimmune disease of the hair follicle.4 The lesion occurs as a result of a local T-cell–mediated cytotoxic inflammatory response that includes CD4+ T lymphocytes, CD8+ T lymphocytes, and natural killer cells.5

Alopecia areata is caused by a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers.4 The genetic predisposition is suggested by familial aggregation and high concordance rate in monozygotic twins.2 Patients with HLA-DR4, HLA-DR5, HLA-DR6, and HLA-DQ3 are more susceptible to alopecia aerata.4 Twin studies have suggested that environmental factors are also operative.1

Children with emotional stress are at risk for alopecia areata. Emotional stress might act as an initiator of neurogenic inflammation critical for the development of the cytotoxic reaction pattern.5

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

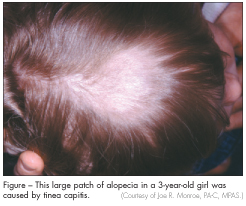

In trichotillomania, the morbid impulse to pull out one’s own hair, the hairs are broken at various lengths; there is no scaling or erythema of the scalp. In tinea

capitis, the diagnosis is suggested by erythema, scaling, and crusting locally on the scalp (Figure). Trichorrhexis nodosa is characterized by the development of grayish white nodules on the hair shaft, through which the shaft is easily fractured.

MANAGEMENT

Because of the high rate of spontaneous recovery, especially in children with little hair loss or a recent onset, conservative management with a watch-and-wait approach is often recommended. Reassurance and psychological support, if necessary, may be offered.

For patients who actively desire treatment, a topical mid-potency corticosteroid, with or without minoxidil, is the therapy of choice.1 Other therapeutic options include intralesional corticosteroids and topical immunomodulators (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus).1

This patient’s alopecia was managed conservatively. The hair grew back in about 10 months.

PROGNOSIS

Although alopecia areata is often transient, its course is unpredictable and it can recur.1 Poor prognostic factors include younger age of onset, prolonged hair loss, extensive hair loss, ophiasis, nail dystrophy, personal history of atopy, presence of other autoimmune disease, and family history of alopecia areata.1,2

1. Hon KL, Leung AK. Alopecia areata. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2011;5:98-107.

2. Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, et al. Alopecia areata update: part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;

62:177-188.

3. Wasserman D, Guzman-Sanchez DA, Scott K, McMichael A. Alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:121-131.

4. Kos L, Conlon J. An update on alopecia areata. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:475-480.

5. Cetin ED, ¸Savk E, Uslu M, et al. Investigation of the inflammatory mechanisms in alopecia areata. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:53-60.