Peer Reviewed

A Case of Anaplasmosis During the COVID-19 Pandemic

AUTHORS:

Tiffany Kurian, BS, MS1 • Sashi Makam, MD1,2,3

AFFILIATIONS:

1Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine, Middletown, New York

2Mid Hudson Medical Research, New Windsor, New York

3Horizon Family Medical Group, New Windsor, New York

CITATION:

Kurian T, Makam S. A case of anaplasmosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consultant. 2021;61(7):e24-e25. doi:10.25270/con.2020.11.00006

Received August 25, 2020. Accepted September 25, 2020. Published online November 3, 2020.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Sashi Makam, MD, Horizon Family Medical Group, 17 Oakwood Terr, New Windsor, NY 12553 (smakam@mhmresearch.com)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a 72-year-old New York woman with an extensive history of cancer presented to her primary care physician via telemedicine with concern for a 1-day history of generalized fatigue, fever, chills, and muscle aches. The patient was instructed to undergo a nasopharyngeal swab test for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19; she was advised to self-treat symptomatically and to remain quarantined pending the test results. After 3 days, her symptoms had not improved, and she had significant weakness and dizziness, leading her to fall. The patient was then advised to go to the local emergency department (ED) for further evaluation.

Physical examination. In the ED, the patient’s physical examination findings were unremarkable except for a low-grade fever (temperature, 37.8 °C). She reported having fever, chills, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. She denied having dyspnea, cough, or a wheeze. She had not noted any changes in her sense of smell. However, she was found to have elevated levels of creatine kinase, lactate, liver enzymes, and troponin. She was admitted into the hospital for further evaluation for a possible COVID-19–related illness.

History. The patient reported that she had been mowing the lawn 1 day prior to the onset of symptoms. During further interviewing, the patient reported having sustained a tick bite on her right thigh 7 days prior to her telemedicine visit, and she was unsure if she had properly removed the tick. However, the patient had not reported this incident during her initial telemedicine appointment.

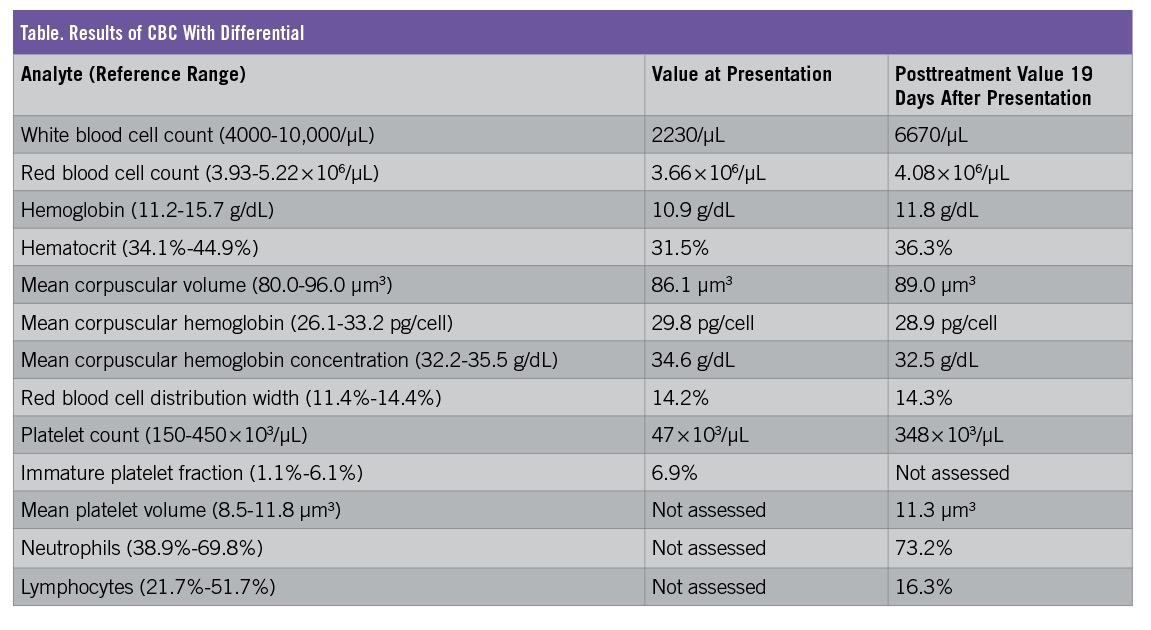

Diagnostic tests. The results of a COVID-19 reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction nasopharyngeal swab test performed 1 week prior to presentation, as well as of a test performed in the ED, were negative. Lyme disease western blot test results also were negative. Blood and urine cultures were negative for pathogens. The results of 2 complete blood cell counts (CBCs) with differential, taken before and after treatment, are reported in the Table.

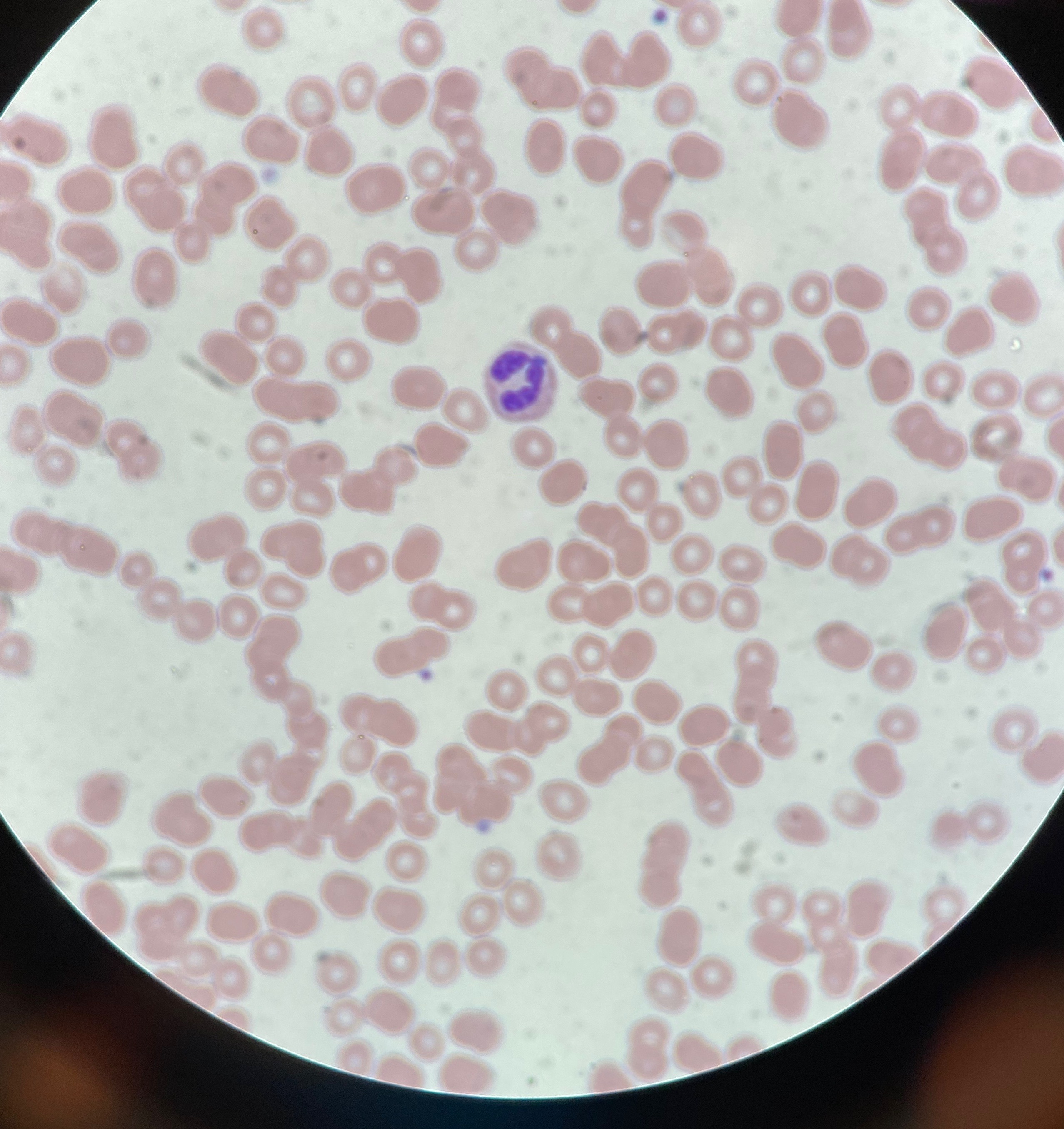

The patient’s peripheral smear results identified Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Figure).

Figure. The patient’s peripheral blood smear showing anaplasmosis as evidenced by intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Giemsa stain, original magnification ×100).

Outcome of the case. Based on the clinical history, laboratory findings, and peripheral smear results, a diagnosis of anaplasmosis was established. The patient was treated with a course of oral doxycycline and intravenous ceftriaxone, which she tolerated well. She was discharged from the hospital on day 5 on a 21-day course of oral doxycycline and was advised to follow up with her primary care physician. At follow-up 19 days after presentation, her CBC findings had returned to normal limits after treatment, and her symptoms had improved.

Discussion. Clinical practice is centered around obtaining a detailed history, given that more than 80% of diagnoses are reportedly made based on history alone.2 In this patient’s case, if the information about the tick bite had been obtained at an earlier stage, the patient’s anaplasmosis may not have rapidly progressed. Thus, when a patient presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, and myalgia, it is important to also take into account the geographic area and season, since tickborne diseases are especially prevalent during the spring and summer seasons in the US Northeast.1

Anaplasmosis is caused by the intracellular bacterium A phagocytophilum. The bacteria are transmitted through the Ixodes scapularis tick in the Northeast and the Ixodes pacificus tick in the Midwest. An individual can experience minor symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgia, nausea, and diarrhea 1 to 2 weeks after the tick bite; untreated, these symptoms can progress to respiratory difficulty, coagulopathies, and organ failure. The diagnosis is made by way of a blood test, but clinicians may treat the disease with empiric antibiotics while awaiting test results. Doxycycline is the recommended treatment for children and adults alike. Disease prevention is through proper examination of the clothes and body, as well as examination of pets, to ensure that no tick has latched on.1,3

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of reported cases of anaplasmosis rose steadily from 348 cases in 2000 to a peak of 5762 cases in 2017, although the agency noted that the number of reported cases in 2018 was substantially lower, at 4008 cases.1 Despite the increase in reported anaplasmosis cases, the mortality rate remains below 1%.1

In order to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment and to continue to keep mortality rates low, tickborne diseases such as anaplasmosis—the clinical presentation of which has much overlap with that of COVID-19—should be on the list of differential diagnoses for patients who present with nonspecific symptoms.

REFERENCES:

- Anaplasmosis: epidemiology and statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed March 26, 2020. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/anaplasmosis/stats/index.html

- Henderson R. History and physical examination. Patient.info. Edited November 24, 2014. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://patient.info/doctor/history-and-physical-examination

- Sexton DJ, McClain MT. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. UpToDate. Updated September 16, 2020. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/human-ehrlichiosis-and-anaplasmosis