Mucocutaneous Drug Reactions

Photo Essay

A Collage of Images on a Clinical Theme

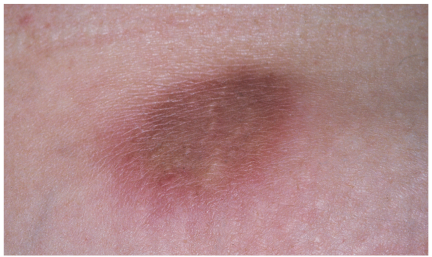

Panniculitis

Panniculitis

Marc Gonka, MD

Painful, erythematous plaques had erupted 4 to 6 weeks earlier on the left upper arm and lower abdominal wall of a 54-year-old woman. The lesions had since increased in size and become more tender.

The patient reported no trauma, fever, chills, sweats, arthralgias, myalgias, or weight change. Her past medical history included embolic stroke, hypertension, and intravenous substance abuse. While taking warfarin 1 year earlier, she had been given one injection of vitamin K subcutaneously at each of the sites of the current lesions for a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio. Other than the plaques on her left arm and abdominal wall, physical examination findings were unrevealing.

Complete blood cell count, chemistry survey results, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were normal. There was no evidence of absolute or relative eosinophilia. An injection of triamcinolone into a single lesion failed to relieve the pain significantly.

A 3-mm punch biopsy of one abdominal lesion was obtained. Histologic examination revealed dermal sclerosis and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate extending into the subcutaneous tissue. The differential included morphea, lupus profundus, and injection site panniculitis. A diagnosis of vitamin K panniculitis was made.

Cutaneous reactions to vitamin K are rare, but a number have been reported, particularly in persons with underlying liver disease, such as cirrhosis, hepatitis, hepatoma, and Budd-Chiari syndrome. It is unclear whether the higher incidence of cutaneous vitamin K reactions in these patients is secondary to hepatic pathology or caused by the increased need to replenish vitamin K in advanced liver disease.

Two classes of cutaneous reactions are known. The first is characterized by erythematous, indurated, pruritic plaques that occur 24 to 48 hours after vitamin K injection. This reaction is thought to be caused by a delayed-type hypersensitivity. The lesions resolve within weeks.

The second class of reactions arises between 1 month and 2 years postinjection. The eruptions are described as sclerodermoid. Some sclerodermal changes associated with this type of reaction may fail to resolve. Some patients with this type of reaction do not experience pain.

Surgical consultation and excision of painful lesions may be considered. This patient declined surgery and was referred to a pain management clinic.

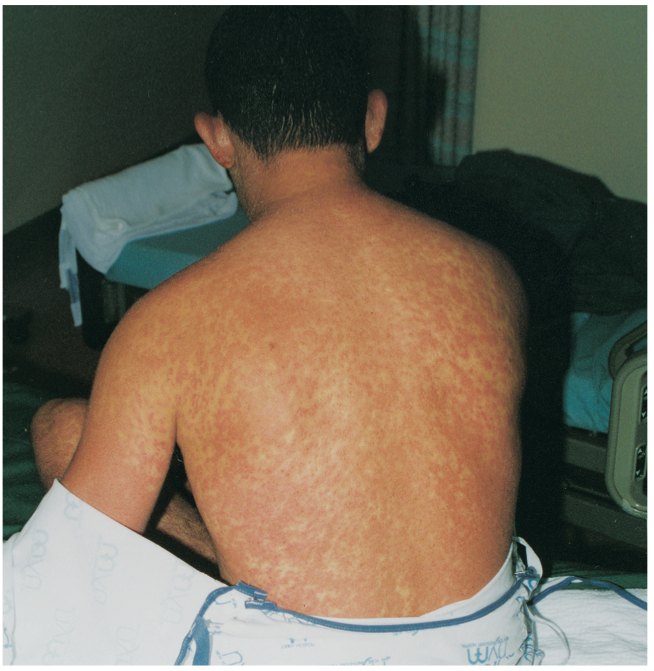

Hypersensitivity Reaction

Renuka Borra, MD and Thomachan Kalapura, MD

A 25-year-old man presented with an erythematous, pruritic, scaly, macular rash that had begun behind his ears and spread over his neck, chest, trunk, and upper and lower extremities. The palms and soles were spared.

The patient was febrile (temperature, 38.7°C [101.7°F]) and had a dry cough for 1 day, generalized lymphadenopathy, and a congested pharynx. He denied nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or abdominal pain, weight loss, headache, neck stiffness, joint pains, and urinary symptoms or urethral discharge.

The patient had been taking phenytoin for the past 2 months to prevent post-traumatic seizures. He denied travel, exposure to pets, and any history of arthropod bites. He had multiple sexual partners.

White blood cell count was 15,200/mL with 15.6% eosinophils. Serum chemistry test results were within normal limits. The patient was seronegative for HIV. VDRL testing was also negative, as were blood cultures and viral titers for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and rubella and rubeola viruses. The differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, acute retroviral syndrome, infectious mononucleosis, gonococcemia and meningococcemia, and acute viral exanthema. The results of the work-up confirmed that this patient had phenytoin hypersensitivity syndrome.

This is a potentially fatal hypersensitivity syndrome that manifests with cutaneous and systemic reactions to the arene oxide–producing anticonvulsants phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital sodium. The condition apparently is caused by an inherited deficiency of epoxide hydrolase, an enzyme

required for metabolism of a toxic intermediate arene oxide formed during phenytoin metabolism by cytochrome P-450. Since the syndrome may be genetically determined, siblings can be at increased risk.

Early recognition of the syndrome, which has various presentations, is key to management that requires immediate cessation of the anticonvulsant and close monitoring of the patient. A benzodiazepine may be substituted for seizure control; gabapentin and lamotrigine also can be used.

Signs and symptoms of the phenytoin hypersensitivity syndrome may include scarlatiniform or morbilliform rash, fever, facial and tibial edema, tender generalized lymphadenopathy, leukocytosis (often with atypical lymphocytosis and eosinophilia), hepatitis and, occasionally, nephritis. Anemia, pharyngitis, and diarrhea also may be present. Pulmonary involvement is uncommon.

Cutaneous reactions normally begin 1 to 3 weeks after phenytoin therapy is initiated and resolve rapidly with cessation of the culprit anticonvulsant and treatment with systemic corticosteroids. Systemic glucocorticoids (prednisone) reduce signs and symptoms as well as laboratory evidence of severe hypersensitivity reactions. Complete resolution of all symptoms of the phenytoin hypersensitivity syndrome with systemic corticosteroids has been reported.

Lichenoid Drug Eruption

Charles E. Crutchfield III, MD, Sarah T. B. Seidelmann, MD, and Humberto Gallego, MD

A 54-year-old Asian woman complained of itching from a newly erupted rash. The purple papules and plaques were symmetrically distributed on the patient’s back, arms, and legs (A and B).

A 54-year-old Asian woman complained of itching from a newly erupted rash. The purple papules and plaques were symmetrically distributed on the patient’s back, arms, and legs (A and B).

Microscopic examination of material from a lesion showed spongiosis (edema surrounding the individual keratinocytes in the epidermis) and a bandlike, chronic inflammatory infiltrate at the dermal-epidermal junction (C). In addition, apoptotic, or dying, keratinocytes were noted at the basal layer of the epidermis.

Hypertension had been diagnosed in, and a thiazide diuretic prescribed for, this patient a few days before the lesions appeared. The cutaneous outbreak was diagnosed as lichenoid eruption caused by thiazides.

Typically, a medication exanthem arises on the trunk and upper extremities; less commonly, the rash erupts on the lower extremities and genital region. The disease is called lichenoid because of its clinical and histologic similarity to lichen planus. As in lichen planus, the mucous membranes can be involved. The medications that are most often associated with a lichenoid drug eruption are angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, penicillamine, gold, antimalarial agents, thiazides, b-blockers, and tetracyclines.

This patient’s thiazide agent was replaced by a drug of a different class. Application of a topical corticosteroid for symptom relief was not necessary. The rash resolved 2 weeks after the offending agent was stopped.